From the February 1994 issue of Car and Driver.

Put any car guy under the microscope, zoom down through his polite and civilizing layers to where the corpuscles flow red hot, and there burns The Universal Fantasy: You get a surpassingly neat car, then you make it even neater.

This is a field trip into that fantasyland.

But first, let’s agree on what constitutes “neater.” Can we drop all pretense at high-mindedness? Truth be told here, the satisfactions we’re chasing aren’t much above scheming to get the biggest slice of the pizza. And then getting it!

Give us more of the good stuff!

More power. Speed thrills.

More grip. G’s thrill.

What else is there?

Ah, now here is the leading question.

The fantasy cars we’re seeking don’t exist on any menu. They’re cooked to order. So, what’s the chef’s latest inspiration? Give him some room, we say. Let’s see what he can do.

That’s what happened here. We called a meeting of the best car chefs—tuners, in the parlance. “Cook something up for us,” we said. “Show us maximum neat. Bend our mind, blow our fuses.”

For a meeting room, we reserved the state of Texas. Lots of space down there, too much, heh, heh, for really good police protection on all the blacktops. For the exacting demands of testing, we bought a day on the Firestone test track at Fort Stockton.

Clearly, this would be a go-fast meeting. But we wanted real cars, not racing cars. So we threw down two requirements to assure that these Chef’s Specials would be good citizens of the automotive world. First, they had to be emissions legal. That means the tuners had to demonstrate that their engine-modification packages passed the standard EPA emissions test, which would make them 49-states legal, or that they certified them with the tougher California Air Resources Board, which is accepted by the feds.

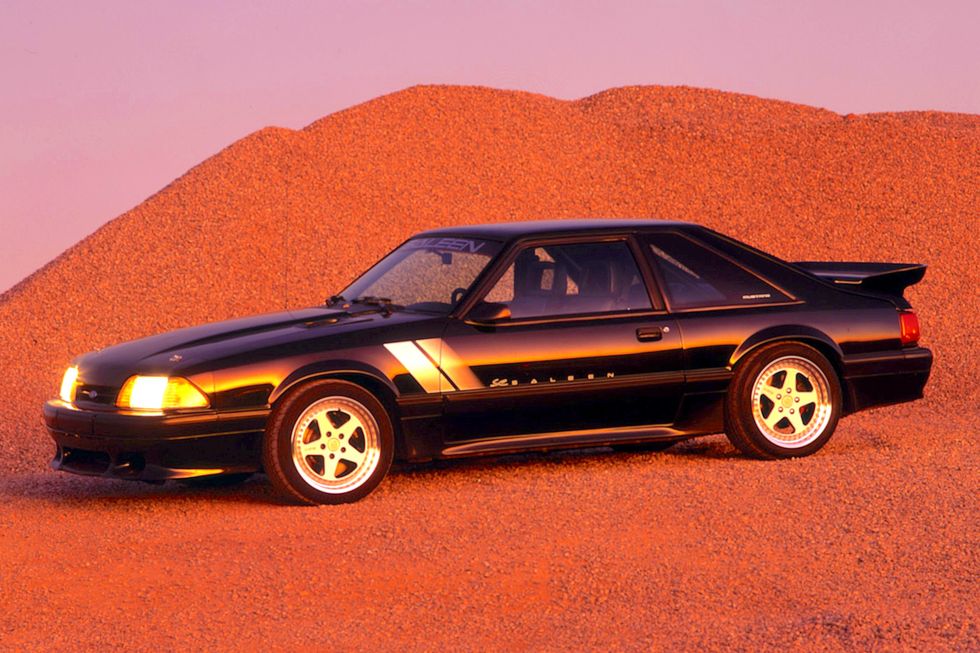

Saleen Mustang

Sometimes the thing just blows up.

Even the best-made plans often go awry when it comes to driving and testing a group of supertuned cars. No matter how much preparation goes into the endeavor, there’s always something that goes wrong. Unfortunately, this time it was the Saleen entry that blew up. It suffered a fatal clutch failure early into our second day of cross-country roadwork and thus never made it to the instrumented testing.

Having sold all of his ’93 Mustangs and with the ’94 models still a few months away from production, Steve sent a ’91 model borrowed from a customer. It came equipped with a 302-cubic-inch (4.9-liter) V-8 sporting a Vortec supercharger, TFS high-performance cast-iron heads, and Saleen Racecraft low-restriction intake manifold, dual exhaust system, and performance chip. Added up, the engine modifications are claimed to produce 425 hp, which is 190 hp more than the last Mustang Cobra we tested.

Exterior modifications included a composite hood, deeper front air dam, lower body-side cladding, and a large rear wing.

Suspension and brake modifications consisted of stiffer springs, shocks, and bushings, plus larger rotors and calipers both front and rear. Rounding out the mechanical modifications were shock-tower braces and a set of seventeen-inch wheels shod with low-profile BFGoodrich Comp T/A tires. Interior changes were limited to a roll cage, racing harnesses, and some additional gauges. In all, the modifications made for a seemingly strong contender with an aggressive stance, good looks, and a sweet sound coming from the pipes.

Due to the clutch failure, our only impressions of the Saleen were gathered during our first day of over-the-road driving on the cross-country leg of the program into New Mexico. Although the engine felt strong and pulled impressively at the start of our drive, its output and performance seemed to wane as the day wore on. Soon after our lunch stop, on the first really twisty section of road, the engine began to blow oil out the rocker cover vent, and the V-8’s output faded. At day’s end, it was fully winded and in need of rejuvenation.

On open stretches, interstates, and two-lane blacktop, the Saleen tracked straight, exhibiting none of the usual dartiness common to cars equipped with wider tires. The stiffer suspension underpinnings and low-profile rubber increased ride harshness, but not intolerably, over that of a stock Mustang GT. Handling, however, was less than perfect on the twisty mountain road sections of our drive. Under hard cornering, the rear end tended to wiggle and squirm like Bob Packwood at a NOW convention. A loud grinding sound emanating from the aft end only added to our sense of unease.

Coming on the heels of the aftermarket industry’s annual SEMA show, our gathering proved to be troublesome for Saleen, because his only cherry car had to be in Las Vegas on display. The poor showing of this entry was probably due more to the car’s high mileage and heavy usage than to his modifications and workmanship. But as we’ve said before, when it comes to aftermarket tuners, caveat emptor. —André Idzikowski

SPECIFICATIONS

Vehicle type: front-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 4-passenger, 3-door coupe

Price, stock (1993)/modified (1991): $19,900/$31,278

Engine type: 16-valve V-8, iron block and heads, port fuel injection

Modifications (1994 prices): engine: Vortec supercharger, low-restriction intake manifold, high-performance heads (oversized valves), 1.72 roller rockers, low-restriction dual exhaust system, performance chip, ($5267); short-throw racing transmission with 3.00:1 final-drive ($1684); suspension: stiffer springs and shocks, bushings, shock-tower braces, underbody subframe connectors ($1110); brakes: four-piston front calipers with 13-inch grooved rotors, 2-piston calipers with 10.5-inch vented rotors, stainless lines ($2495); wheels and tires: 17-inch Saleen 3-piece alloy wheels, BFGoodrich Comp T/A tires ($2695); body and interior composite hood, air dam, spoiler, side skirts, extra gauges, roll cage, racing harness ($2495)

Power, stock/modified: 235 hp/425 hp

Transmission: 5-speed manual

Curb weight: 3250 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph, stock/modified: 5.6 sec/DNF

1/4-mile, stock/modified: 14.3 sec @ 98 mph/DNF

100 mph, stock/modified: 14.7 sec/DNF

130 mph, stock/modified: 35.3 sec/DNF

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph, stock/modified: 5.9 sec/DNF

Top Gear, 30–50 mph, stock/modified: 11.3 sec/DNF

Top Gear, 50–70 mph, stock/modified: 12.0 sec/DNF

Top Speed (drag limited): 137 mph

Braking, 70–0 mph: 181 ft

Roadholding, 300-ft-dia skidpad, stock/modified: 0.85/DNF

Such certification has another benefit—it pulls this fantasyland within checkbook reach of your armchair. These aren’t one-off powerplants available only to magazine testers. They’re on the market, and any of the chefs would be delighted to cook one up for you.

As for our second requirement, well, you won’t feel too sorry for us. To qualify for the track test, the cars had to live through the roadwork. There’s nothing like hundred-mile stretches of open road, punctuated by stop-and-go metro slogging, to screen out the prima donnas and nickel rockets. Neat cars are supposed to do all the things that ordinary cars do, and more. Not less. So we planned two days of switching seats and blurring the Texas terrain, just to make sure these weren’t one-trick ponies.

When the meeting was called to order in El Paso, six tuners presented their credentials. Many more were invited—including Callaway, Dinan, Hennessey, HKS, and Ruf—but the emissions-legal requirement or logistical problems held them back. Another, the Stillen 300ZX, was felled by an untimely crash.

That left us with a Mustang-to-Mercedes array, $31,278 to $200,000 in full-dress prices. Cheap thrills these aren’t.

Steve Saleen’s supercharged 5.0 Mustang weighed in at the affordable end. Saleen is just now celebrating his tenth anniversary as a “small-volume manufacturer,” a level of truce with the regulators that few special builders ever attain. It permits him to modify zero-mile cars and sell them through new-car dealers. Unfortunately, his makeover of the 1994 Mustang was still a few months off at the time of the meeting. Instead, he sent a high-mileage customer car of the old design.

Peter Farrell Supercars RX-7

The prescription for activist-enthusiasts.

Rally champ turned road racer Peter Farrell launched his aftermarket tuning operation right in the middle of a busy and successful IMSA GT Supercar series, in which he was campaigning Mazda-sponsored RX-7s. It seems that more than a few civilian RX-7 owners were following the race series and developing an acute speed-lust in the process. Naturally, they called Farrell’s race shop in search of a cure. Peter Farrell Supercars Inc. was born to minister to these poor sick souls.

And who better to do so? Of the handful of shops souping up RX-7s, Farrell’s is the oldest and it’s the only one with a direct factory racing connection. PFS owns what may be the only dynamometer outside Japan set up to run ’93 twin-turbo rotary engines, so when Farrell rates his engine at 360 horsepower, you know that it actually makes 105 more ponies than a stocker.

Farrell is a hands-on racer. He’s totally Type A, he wrenches what he runs, and he doesn’t just send his chief mechanic along on trips like this—he comes himself. It naturally follows that his car, which is clearly the most adjustable one of the bunch, encourages the active involvement of its driver.

Progressive-rate springs and adjustable shock absorbers with eight settings provide ride comfort that ranges from RX-7 Touring-soft to firmer than a stock R2. Quite a bit more understeer has also been baked in to make the car more user-friendly for the non-racer.

High-volume intake and exhaust systems and a larger, more efficient intercooler provide the potential for big speed. It’s Farrell’s magic software that allows the engine to fulfill that potential. Most tuners provide an engine computer chip with a high-performance calibration programmed in. The PFS computer comes with three performance calibrations, each optimized for a different set of operating conditions (plus a no-boost “valet” mode). But if you can demonstrate to Farrell that you’re smart enough to handle it, he will sell you the almost infinitely programmable model we tested.

This baby allows fine tuning of the fuel, boost, and ignition maps for operating conditions outside those encountered on the government’s emission cycle. Air too thin at high altitude? Dial in a bit more boost and less fuel. Can’t find 92-octane fuel? Dial back the spark and boost. The car is always adjusted to get max power for the conditions.

So tuned, this RX-7 runs like a rocket. Big power lives in the secondary turbo that chimes in at over 4500 revs to lift boost levels as high as 15 psi, so quick sprints require a vicious clutch drop. The top speed of 170 mph was measured after two attempts were aborted, due to a failed hose clamp on the boost-pressure relief valve and an oil breather line that burst after g-forces filled it with oil in the banking on our 7.5-mile track. But Farrell doesn’t compete on drag strips or the Bonneville Salt Flats—he’s a road racer. So it’s no surprise that his car cleaned up on the road course: here, despite strong understeer, the RX-7 turned in the best lap time by 0.8 second. A tuned car that’s both faster and more forgiving than stock with no comfort penalty—sounds like good medicine to us. —Frank Markus

SPECIFICATIONS

Vehicle type: front-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2-passenger, 3-door coupe

Price, stock (1994)/modified (1993): $36,758/$47,203

Engine type: twin-turbocharged and intercooled 2-rotor Wankel, aluminum rotor housings iron end plates, port fuel injection

Modifications (1994 prices): engine: larger intercooler with larger and more rigid ducting, low-restriction intake system, driver-programmable powertrain-management computer, low-restriction exhaust system aft of stock catalytic converter ($3500); short-throw shifter kit and 4.30:1 rear-axle gearset ($1000); suspension: progressive-rate springs, 8-position adjustable shocks, stiffer anti-roll bars ($1500); brakes: Kevlar pads, stainless lines ($450); wheels and tires: 17-inch O.Z. Mito 3-piece modular wheels, Bridgestone Comp T/A tires ($3800); body: front fascia, rear spoiler ($1290)

Power, stock/modified: 255 hp/360 hp

Transmission: 5-speed manual

Curb weight: 2848 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph, stock/modified: 5.3 sec/4.3 sec

1/4-mile, stock/modified: 14.0 sec @ 100 mph/12.9 sec @ 112 mph

100 mph, stock/modified: 14.0 sec/10.7 sec

130 mph, stock/modified: 27.4 sec/18.3 sec

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph, stock/modified: 5.9 sec/5.3 sec

Top Gear, 30–50 mph, stock/modified: 13.4 sec/10.9 sec

Top Gear, 50–70 mph, stock/modified: 7.9 sec/5.8 sec

Top Speed (drag limited), stock/modified: 157 mph/ 170 mph

Braking, 70–0 mph, stock/modified: 156 ft/164 ft

Roadholding, 300-ft-dia skidpad, stock/modified: 0.99/0.95 g

John Lingenfelter, naturally, was ready. He’s a racer—by instinct a predator, no more able to hide his intentions than an eagle circling in the sky. He’s 48 now, an eminence with steel-gray hair: for a quarter of a century he’s been building engines to put in fast cars, many of them his own, for the sole purpose of beating all comers, at the drags mostly. His shop in Decatur, Indiana, specializes in powertrains, usually Chevy V-8 because that’s what the market wants, but his talent finds horsepower in whatever the customers bring to his door.

He doesn’t hide from the bureaucratic procedures, either. His standard tweak of the Corvette LT1—displacement stretched to 383 cubic inches (6.3 liters) output upped to 440 horsepower—has passed all the emissions tests necessary for CARB acceptance. The black Corvette he unloaded in El Paso was specially built for the occasion—rented, actually, from Bud’s Chevrolet in St. Marys, Ohio, and reloaded with a Lingenfelter 383. What we thought of as a meeting, he viewed as a shootout. And he came, as usual, cocked and locked.

Minneapolis Corvette specialist Doug Rippie brought a black Corvette too, a ZR-1, seemingly stock at first glance. Then you notice the big-bore exhausts and the roll bar. Rippie is 43, barb-wire lean, reserved at first, like a midwestern farmer. His shop does “anything for Corvettes,” but road racing is the passion. He parked his own helmet after the 1986 season to concentrate on preparing cars for others. He’d comprehensively massaged this ZR-1 for its owner, 22-year-old Steve Wait, to run in the Silver State 100 last May. Wait drove it to a seventh-in-class finish, averaging 159.4 mph on his first try at this public-road display of bravery that occurs twice each year.

Lingenfelter Covette

Walk softly and carry a big broom.

Among the brightly colored, bespoilered entries in this test, John Lingenfelter’s Corvette sticks out like a healthy, normal thumb. There’s little clue to this car’s speed other than its shiny ZR-1 wheel—sort of like Clark Kent with little dumbbell cufflinks. Lingenfelter likes the subtle approach. Ask him what his Corvette will do, and he’ll defer until he sees the numbers. He prefers to let the machinery speak for itself.

Experienced drag racers (or, the ones who know better) are aware of the peril of prediction. You could call 48-year-old Lingenfelter experienced, with twelve NHRA class championships under his belt. He even worked as an engineer for International Harvester for seven years. But Lingenfelter is best known for the reworked Chevy Corvettes, from small block to ZR-1, which have left his Indiana shop since 1987. For this exercise, he worked up a standard LT1 coupe, because he thought more readers would be interested in it.

Lingenfelter works hardest on what he knows the best: the engine. This car includes his bored, stroked, and blueprinted 383-cubic-inch (6.3-liter) engine, with its hotter cam, and reworked intake and exhaust system . It makes 440 horsepower (140 more than stock) at 6000 rpm.

Lingenfelter included ZR-1 tires, wheels (polished at a local shop), anti-roll bars, and springs, because he likes their ride and handling. He also wanted the ZR-l tires’ 200-mph speed certification. To fit the wide wheels in the stock fenders and to maintain proper wheel offset, the rear spindles are machined.

This Corvette drives as if it were on some illicit drug. The torque, all 450 pound-feet of it at 4500 rpm, might as well be anywhere on the tach—down low, in the midrange, or near the 6500-rpm redline. The exhaust howls, and the body squirms with each shift, giving this car an uncanny liveliness. In acceleration tests, the tires want to go up in smoke in second gear. Lingenfelter suggests we shift at 6300 rpm. Spin the tach past 6000 rpm, where its markings end, and the needle starts bouncing, as if to say, “Hey! What the hell’s going on down there?” Top speed, with the engine in full baritone wail, is 189 mph.

The tire and wheel swap made for better roadholding and braking but did not translate to faster track laps. With the prodigious underhood juice, Lingenfelter’s car required restraint in corners. When the tail did swing wide, it would recover with a hard snap. “This car requires a careful and deft touch,” said tester Csere. Still, Lingenfelter’s car matched the lap times of Rippie’s smooth-handling ZR-1. As drag racers will remind you, power counts for a lot.

Lingenfelter seemed relaxed throughout the test, probably because his car, which needed little fiddling, seemed so well prepared. He even came prepared with a broom to sweep the track for the acceleration tests. Something his car did handily, as well. —Don Schroeder

SPECIFICATIONS

Vehicle type: front-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2-passenger, 3-door coupe

Price, stock (1994)/modified (1993): $40,074/$59,260

Engine type: 16-valve V-8, iron block and aluminum heads, port fuel injection

Modifications (1994 prices): engine: bore +1 mm, stroke +7 mm, heads and intake manifold ported and polished, high-performance cam, performance chip, low-restriction exhaust system aft of catalytic converters ($16,800); suspension: ZR-1 front and rear springs, custom-valved shocks, stiffer anti-roll bars ($1255); brakes: 4-piston front calipers, 12.9-inch grooved and cross-drilled front rotors, stainless-steel lines ($3182); wheels: polished 1994 ZR-1 ($2363)

Power, stock/modified: 300 hp/383 hp

Transmission: 6-speed manual

Curb weight: 3368 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph, stock/modified: 5.4 sec/4.2 sec

1/4-mile, stock/modified: 14.0 sec @ 103 mph/12.4 sec @ 119 mph

100 mph, stock/modified: 13.2 sec/9.0 sec

130 mph, stock/modified: 26.3 sec/14.7 sec

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph, stock/modified: 5.8 sec/4.3 sec

Top Gear, 30–50 mph, stock/modified: 12.0 sec/8.7 sec

Top Gear, 50–70 mph, stock/modified: 12.2 sec/9.1 sec

Top Speed (drag limited), stock/modified: 158 mph/189 mph

Braking, 70–0 mph, stock/modified: 176 ft/167 ft

Roadholding, 300-ft-dia skidpad, stock/modified: 0.89/0.95 g

In addition to the gasoline in his veins, Rippie has computers in his mind, the result of computer school in his younger days. Now he’s fearless when it comes to engine-management black boxes. His ZR-1 package, rated at 475 horsepower from the stock 5.7-liter displacement, is emissions legal in all 50 states.

Twinkly-eyed Peter Farrell, 35, is a racer, too, so much so that he left his native New Zealand ten years ago to pursue the bigger possibilities of the U.S. Along the way, he hooked up with Mazda to campaign the new RX-7 in road racing. Now he’s applying what he’s learned on the track, and his own intuition about what street drivers really want, into a go-fast, handle-sharp package for the RX-7 that he calls the Peter Farrell Limited Edition.

Farrell’s good-humored approach makes him seem less of a gunslinger than the Corvette racers. But steer the conversation toward the politics of IMSA racing and watch him ruffle up like a banty rooster. Racers—good ones, anyway—are all alike under the skin. They thrive on advantage: finding it, seizing it, using it to make others small in the rear-view mirror. His engine mods, which boost the RX-7’s output by 105 horsepower to 360 horsepower, are legal in 49 states, and the paperwork has been filed for California.

As the players lined up for the first sortie out of El Paso, the pea-shooter rotary—as it turned out, the only runner with less than 400 horsepower—was the consensus underdog. Rotary engines have always been inscrutable to piston guys. Over the years, though, we’ve learned that inscrutable is not the same as impotent.

DR Motorsports Corvette ZR-1

Fine-tuning without fanfare.

The three-inch exhausts poking out the back of this ZR-1 sing a gloriously throaty basso profundo, and they jump the needle on the dyno by 17 horsepower, yet we have the idea Doug Rippie allows them in the car with a certain reluctance. Before leaving his Minneapolis shop, he’d tried to conceal them with a spray of flat black. Showing off—hell, showing anything—is not his style.

“Not interested,” is all he has to say about the deep chin spoilers, wings, spats, slats, slits, and strakes that dress up—and less often enhance the performance of—some cars. That stuff all runs against his grain.

He messes with the looks only when he gets performance. The Dymag cast-alloy wheels are made to his specification—0f magnesium to reduce weight, of non-standard offsets to make the track width one inch wider in front, one inch narrower in back. This brings these dimensions closer to one of his chassis-tuning axioms—to avoid greatly dissimilar front and rear track dimensions.

Rippie, at heart, is a chassis tuner, even though his engine business is now as big as his chassis business. Twenty years of road racing does that, just because road courses are a lot more fun in cars that turn and brake as athletically as they accelerate. He began tuning the current-model Corvette eight years ago. He learned well. This Corvette, in the twisties, pretends it’s not a Corvette.

In fact, among the staffers, this may prove to be a watershed Corvette. The stock version has tremendous grip, but it’s full of transitional wiggles that accompany changes of brake, power, and steering inputs. Though these wiggles don’t fling you off the road, they’re unsatisfying to perfection seekers and, at very least, they encourage leaving big margins next to mountain dropoffs. Those among us who were impressed by Corvette grip tended not to admit the wiggles—until they finally drove a Corvette that doesn’t wiggle. This one.

In the mountains, this is a precision tool, with very good path accuracy. On the road course—after the top-speed run, when the engine was whipped—it matched the lap times of the more powerful Lingenfelter car without the yawing histrionics. Doug Rippie has this chassis figured out.

His list of modifications (in condensed form here) is extensive: coil springs in place of the plastic leaves; drastically-reduced bump steer both front and rear; less static caster; less brake anti-dive; more camber gain in front, and less in back; and harder bushings in certain pivots. The whole package costs over $23,000—but it makes a terrific Corvette.

On the road, particularly when Rippie experimentally dialed an altitude correction, the engine felt like its full, rated, 475 hp. But during sustained full-throttle testing, the engine suffered from a mysterious fuel restriction that strangled its output the faster it went. The problem was so severe that we couldn’t complete a top-speed run.

Still, we’re impressed. The drastic improvement in handling shows just how much a good chef can contribute. —Patrick Bedard

SPECIFICATIONS

Vehicle type: front-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2-passenger, 3-door coupe

Price, stock (1994)/modified (1991): $71,538/$90,932

Engine type: DOHC 32-valve V-8, aluminum block and heads, port fuel injection

Modifications (1994 prices): engine: ported and polished intake plenum, manifold, and cylinder heads, low-restriction exhaust system, performance chip, heavy-duty clutch ($12,495); 3.73:1 rear-axle gearset ($895); suspension: revised front and rear suspension geometry, coil springs (replace transverse leaf springs and lower ride height one inch), revised valving for 3-position cockpit-adjustable shocks, bushings ($3745); brakes: stock calipers reinforced, rear brake bias spring, stainless lines ($695); wheels: 18-inch Dymag magnesium wheels ($4000); body: roll-cage and racing harness ($1325)

Power, stock/modified: 405 hp/475 hp

Transmission: 6-speed manual

Curb weight: 3546 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph, stock/modified: 4.7 sec/4.3 sec

1/4-mile, stock/modified: 13.1 sec @ 111 mph/12.7 sec @ 115 mph

100 mph, stock/modified: 10.6 sec/9.5 sec

130 mph, stock/modified: 18.3 sec/16.6 sec

150 mph, stock/modified: 28.3 sec/27.1 sec

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph, stock/modified: 5.3 sec/4.9 sec

Top Gear, 30–50 mph, stock/modified: 12.9 sec/11.4 sec

Top Gear, 50–70 mph, stock/modified: 12.9 sec/11.5 sec

Top Speed (drag limited), stock/modified: 179 mph / N/A

Braking, 70–0 mph, stock/modified: 161 ft/165 ft

Roadholding, 300-ft-dia skidpad, stock/modified: 0.92/0.94 g

If engine output were proportional to moving parts, the SOHC V-12 BMW would be a fearsome competitor. AutoThority Performance Engineering of Fairfax, Virginia, had been rubbing on a BMW 850i for some time—on the engine and on the cosmetics. The goal was a “smooth, quiet, tractable, and emissions-legal car,” according to company spokesman Paul Misencik, and, of course, one that was “considerably more powerful.”

Although AutoThority has had its name on a few racing cars over the years, it’s not a race place. From its beginning in the mid-Seventies as a service and tuning shop for Porsches, it progressed into recalibrated engine-management chips for many European and Japanese brands. Now it has complete engine-building and car-modifying facilities, though they are minor enterprises compared with the chip business.

Nonetheless, it has produced an 850i that makes a strong impression even before its V-12, stroked to 5.5 liters from 5.0, comes to life. The aero mods to the nose, sills, and rear, all painted tuxedo black to match the body, give it a sleek, muscular presence they’d barely recognize down at the BMW store. The ultra-low-profile Pirelli P-Zero tires on 18-inch wheels fill the openings just right. The overall look manages what may be a first in the realm of custom cars, to tell the world “one of a kind” in tones that whisper.

The flamboyant-yellow RENNtech-modified Mercedes 500SL says one-of-a-kind too, albeit with the question “Who else would dare?” German-born Hartmut Feyhl started young, at age seventeen, as an apprentice at Mercedes-tuner AMG in Affalterbach, Germany. He stayed with AMG for eleven years, gaining experience, developing information sources at Mercedes engineering and elsewhere. AMG transferred him to the U.S. as technical director, a position he held for two years before starting RENNtech in Delray Beach, Florida, in 1989. Now he’s 32 and determined to succeed on his own.

AutoThority 850i

Pay attention to the man behind the curtain.

Paul Misencik says he’s not the brain trust behind AutoThority—that would be founder Al Collins—but he agrees with the principle behind the company in Fairfax, Virginia, and its 475-horsepower BMW 850i. “Our philosophy is not speed at all cost,” Paul explains. “We want horsepower and refinement.”

That particular axiom might also explain how a 25-year-old who studied philosophy at the University of Maryland came to an outfit that exists to make infinitesimal changes to engine-managing microchips in the search for more horsepower.

Before he studied Schopenhauer, Misencik studied cars. He put himself through the Jim Russell race school at Mont Tremblant in his teens, then raced a Formula Ford for two seasons. He approached Collins for a job after college, when he watched a Collins-modified Porsche 934 in action at Summit Point. Now Misencik is in charge of marketing AutoThority’s doctored chips, but he also gets behind the wheel with engineers in the last stages of chip programming as a guinea pig for the drivability of new projects.

Ninety percent of AutoThority’s business is chip work. With computer software that can plot fuel delivery curves, AutoThority modifies the profile of an engine’s fuel delivery with additional data points. If you’ve got a Mazda, Nissan, or a BMW, AutoThority has probably seen its chips with their pants down.

The other ten percent of its business is special projects like this 1991 850i, owned by a New Yorker who asked for at least 450 emissions-legal horsepower. AutoThority went shopping for the power at Racing Dynamics and picked out a new crankshaft, new pistons and camshaft, a new exhaust system, and eighteen-inch wheels. The stock intake manifold went to California’s Extrude Hone, where gritty gunk was squeezed through its passages to widen and smooth them for better airflow. Finally, all the combustion surfaces—the piston heads, the valves, and the combustion chamber itself—went to New York’s Swain Tech for a ceramic coating.

The result? The AutoThority 850i was 1.2 second quicker to 60 mph, tripped the quarter-mile 1.1 seconds sooner, and topped out 14 mph faster than the governer-limited stocker. The engine work transforms this pudgy battlecruiser into a lithe-lier ride. Because it favors understeer in the twisties, balancing the 850i’s cornering attitude is much easier with 475 horsepower underfoot.

A couple of glitches sullied AutoThority’s upgrades. It occasionally hiccuped under light throttle, and twice it overheated in high-rpm, low-speed corner work. And its tuners expected it to go nearly 190 mph, not the 170 mph we observed. Misencik says this is because the car has two electronic speed limiters and they only disabled one.

Those foibles aside, the AutoThority 850i is bothersome for just one reason. A stock new $94,095 850Ci is already too expensive. The conversions added another $52,000 to the 1991 car. But if you’ve already bought into BMW’s mega-cruiser philosophy, the AutoThority is the next logical step. —Martin Padgett Jr.

SPECIFICATIONS

Vehicle type: front-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2+2-passenger, 2-door coupe

Price, stock (1994)/modified (1991): $94,095/$141,983

Engine type: SOHC 24-valve V-12, aluminum block and heads, port fuel injection

Modifications (1994 prices): engine: stroke +8 mm, compression increased to 10:1, low-friction piston skirts, ceramic-coated piston crowns, valves, and cylinder head surface, performance cams, honed intake manifold, performance chip, low-restriction header and tailpipes ($38,000), 2.93:1 rear-axle gearset ($2000); suspension: lower, stiffer, progressive-rate springs ($800); wheels and tires: 18-inch Racing Dynamics alloy wheels and Pirelli P-Zero tires ($6000); body: air dam, spoiler, side skins ($9000)

Power, stock/modified: 296 hp/475 hp

Transmission: 6-speed manual

Curb weight: 4168 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph, stock/modified: 6.3 sec/5.1 sec

1/4-mile, stock/modified: 14.9 sec @ 96 mph/13.8 sec @ 103 mph

100 mph, stock/modified: 16.6 sec/12.7 sec

130 mph, stock/modified: 31.7 sec/23.7 sec

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph, stock/modified: 6.7 sec/5.5 sec

Top Gear, 30–50 mph, stock/modified: 12.1 sec/9.5 sec

Top Gear, 50–70 mph, stock/modified: 12.2 sec/9.8 sec

Top Speed (governer limited), stock/modified: 156 mph/170 mph

Braking, 70–0 mph, stock/modified: 181 ft/174 ft

Roadholding, 300-ft-dia skidpad, stock/modified: 0.82/0.87 g

After a close inspection of this car, there’s little more that needs to be said about the young Mr. Feyhl, except that he’s quite prickly when things don’t go his way. His car shows supreme confidence; he started for El Paso on a completely untested suspension package (probably his factory contacts eliminated the usual need for trial and error). He’s a perfectionist; modifications throughout the car are highly detailed and beautifully done. He’s aggressive; the name RENNtech appears on the decklid, on the license-plate surround, on the exhaust tips, on the front fenders, on the engine cover, and three times on each hub cover.

As we plugged in our radar-and-laser detectors and made ready for the first day’s 335-mile qualifying thrust into New Mexico’s Mogollon Mountains, what were we to make of this screaming yellow, Hey-look-at-me! Mercedes? High-profile visuals and high-speed muscles, all crammed into the same car, are a worrisome recipe. Might just as well file our route plan with the highway patrol.

The canny Lingenfelter, it should be noted, eyed this car like a loaded gun. He’d encountered Feyhl before, at some past showdown when the German was mothering over another unlikely machine, a big Mercedes transformed into an AMG Hammer—four doors, $160,000 price, top speed over 180 mph. Racers remember feats like that. And they don’t charge them off to luck.

RENNtech 500SL

This Mercedes hot rod shows as well a it goes.

Even a brief glance at the RENNtech 500SL will persuade you that its creator, Hartmut Feyhl, is as much artisan as tuner. His car’s meticulously applied, glorious yellow paint—extending even to the wheel spokes and the arms of the windshield wipers—and his carbon-fiber composite hub caps cannot be overlooked.

A peek inside confirms the notion that this 500SL is as much show car as hot rod. The bright yellow and gray leather interior, with contrasting stitching, covers every interior surface—even the mirror housing. The workmanship is exquisite and the effect is riveting without being garish.

This particular car also uses high-tech composites as interior trim. The panels flanking the transmission tunnel as well as part of the shift knob are carbon-fiber and Kevlar moldings, which are rich, warm, and smooth. The yellowish Kevlar fibers in the gray resin even complement the leather trim.

Feyhl, the head of RENNtech, has devoted considerable attention to the “optical qualities” of his cars—as he puts it in his German-accented speech. But his background includes eleven years at AMG, the premier Mercedes tuning firm in Germany, and his cars reflect AMG’s—and his own—autobahn bloodlines.

Under the hood lies a V-8, punched out from 5.0 to 6.0 liters and fitted with headers, hotter cams, an extrude-honed intake manifold, a low-restriction air cleaner, and catalysts that flow more freely. The result is 440 hp, which flows through a beefed-up four-speed automatic to a 2.47:1 limited-slip differential (stock is 2.65).

Feyhl beefed up the SL’s underpinnings with stiffer and lower springs, thicker anti-roll bars, firmer Bilstein shocks, harder bushings, and beefier brakes and Pirelli P-Zero tires, 245/40-18 in front and 275/35-18s in the rear on 8.5 and 10.0-inch-wide O.Z. wheels.

Feyhl also put the SL on a 400-pound diet by substituting Recaro shell-type seats for the electric-motor infested originals, using lighter sound-proofing, and removing the convertible top and much of its complex mechanism.

These changes transform the 500SL into an explosive hot rod. It hits 60 mph in 4.6 seconds, covers the quarter-mile in 13.0 seconds at 111 mph, and runs solidly into its 6200-rpm cutoff at 182 mph. The RENNtech SL can corner at 0.93 g and stop from 70 mph in 161 feet.

It all adds up to an SL that’s remarkably agile. You can hurl it into corners with confidence and rocket away from the apex while holding the car in perfect balance with the responsive throttle and precise steering.

Despite its performance, the souped-up SL is not a nervous thoroughbred. It idles smoothly, its exhaust note is subdued, and its muscular suspension remains nicely supple. Best of all, the RENNtech SL feels solid enough to run sub-five-second 0-to-60s forever.

The downside to the RENNtech mods is money—they virtually double the SL’s price to about 200 grand. But Feyhl’s workmanship, performance, and refinement simply amplify the original product. You shouldn’t be surprised that his price does the same. —Csaba Csere

SPECIFICATIONS

Vehicle type: front-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2-passenger, 2-door convertible

Price, stock (1994)/modified (1991): $108,148/$200,000 (est.)

Engine type: DOHC 32-valve V-8, aluminum block and heads, port fuel injection

Modifications (1994 prices): engine: bore +4 mm; stroke +6 mm, honed intake manifold and high-volume air cleaner, low-restriction exhaust system ($40,000); 2.47:1 rear-axle gearset ($4000); suspension: lower and stiffer springs, stiffer shocks, larger anti-roll bars, urethane bushings ($10,000); brakes: 4-piston aluminum front calipers with 13.0-inch rotors, 2-piston rear calipers with 12.0-inch vented rotors, stainless lines (incl. w/ suspension mods.); wheels and tires: O.Z. Futura 3-piece composite wheels with Pirelli P-Zero tires ($5500); body: air dams, spoiler, side skirts, custom paint ($10,000, est.); interior: Recaro seats, custom yellow leather trim with carbon-fiber and Kevlar accents ($30,000)

Power, stock/modified: 315 hp/440 hp

Transmission: 4-speed automatic

Curb weight: 3782 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph, stock/modified: 6.3 sec/4.6 sec

1/4-mile, stock/modified: 14.6 sec @ 99 mph/13.0 sec @ 111 mph

100 mph, stock/modified: 15.1 sec/10.8 sec

130 mph, stock/modified: 28.3 sec/18.5 sec

150 mph, stock/modified: N/A / 29.0 sec

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph, stock/modified: N/A / 4.7 sec

Top Gear, 30–50 mph, stock/modified: 3.7 sec/2.8 sec

Top Gear, 50–70 mph, stock/modified: 3.9 sec/2.9 sec

Top Speed (governer/redline limited), stock/modified: 155 mph/182 mph

Braking, 70–0 mph, stock/modified: 175 ft/161 ft

Roadholding, 300-ft-dia skidpad, stock/modified: 0.82/0.93 g

For the record, the road miles were more fun than even the enforcers would imagine, and discretion demands that we leave it at that. But we can declassify a few observations. Consider:

1. Tire makers and chassis tuners are making progress with ultra-low-profile tires. Although such tires still tend to be vague on center, the darty behavior over worn roads that was common a few years ago was not bothersome in any of these cars.

2. Modern fuel injections have altitude-compensating systems to improve performance and economy at high elevations. But there’s still plenty of room for improvement.

3. If your engine demands premium fuel, you still have to plan your trips carefully. We faced empty tanks and towns with only 86 octane in southern New Mexico.

4. It’s amazing how calm and perfectly appropriate three-digit speeds seem when you’re driving the right car on open roads.

5. It’s amazing, too, how much performance is left untapped in today’s production cars.