From the December 1995 issue of Car and Driver.

René Dreyfus, who lived with unique grace for 88 years until August 17, 1993, was one of the last of the legendary Grand Prix drivers from what is often called the Golden Age of motorsport. Ironically, at the time of his death, the race car that brought him to his adopted homeland was in the final stages of restoration in a shop tucked in the hills of western Connecticut.

This massive yet oddly sensuous Maserati 8CTF served as a centerpiece in an epic that transformed Dreyfus from world-class race driver to one of the most renowned restaurateurs in New York, and finally to a living icon among racing aficionados (all of which is recounted in My Two Lives, the autobiography Dreyfus wrote with historian Beverly Rae Kimes a decade before his death).

The elegant single-seater Maserati, chassis-number 3031, was one of three surprisingly potent GP cars built by the Maserati brothers in 1938 to contest the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union panzers under the new, downsized formula of 4.5 liters unblown, 3.0 liters supercharged. The car would go on to numerous appearances at the Indianapolis 500, to win the Pikes Peak hillclimb, and eventually, after meticulous restoration, to live in high profile as part of the vast collection of automotive historian Joel Finn of Roxbury, Connecticut.

Now the 8CTF shrieks and wails again in vintage events across the country, as it did this past summer during a major reunion of prewar Indianapolis cars at the Milwaukee Mile in West Allis, Wisconsin. Running with a nimbleness surprising for its age, it serves as a vital relic of the pinnacles of American and European racing in an unforgettable era.

In 1930, René Dreyfus surged onto the international racing scene, winning the Monaco Grand Prix as an unknown amateur from nearby Nice, beating hometown favorite and France’s best driver, Louis Chiron. His performances throughout the 1930s aboard Bugattis, Alfa Romeos, and Maseratis were consistently good, but his alleged Jewish background (actually, he was Catholic) prevented enlistment by the dominant Nazi-backed Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union teams.

In early 1938, Dreyfus scored his greatest victory on the narrow streets of Pau in the foothills of the Pyrenees. He was at the wheel of an ungainly Delahaye entered by Laury Schell and Lucy O’Reilly Schell, wealthy American expatriates living in Paris and Monaco. She was the brash daughter of an Irish immigrant who had made his fortune in the New World. The pair had moved to Europe in the 1920s and immersed themselves in the world of rallying and amateur sports-car racing. In 1937, after Laury had finished third in the Mille Miglia, they formed Ecurie Bleue in concert with Delahaye, a small but respected Parisian sports-car manufacturer that had created a 4.5-liter V-12-powered car for the new Grand Prix formula.

For the first race of the Grand Prix season, Mercedes-Benz came to Pau with new W154 cars for the team leader Rudi Caracciola and Hermann Lang. Auto Union did not enter, leaving Dreyfus as the only serious opponent. He deftly exploited the Delahaye’s nimbleness and better fuel mileage to win by nearly two minutes.

While fellow Frenchmen were celebrating Dreyfus’s upset, in Italy the three remaining Maserati brothers—Bindo, Ettore, and Ernesto—and their 10-man staff were completing a trio of Grand Prix machines that on paper were the equal of anything in the world. Since the death in 1932 of brother Alfieri, the acknowledged family leader, the Maseratis had established a reputation for technical brilliance and financial blundering. Their output was minuscule compared with that of rivals Alfa Romeo and Bugatti: 16 cars in 1934, 17 in 1935, a mere nine in 1936. But 1937 brought an infusion of money from the Orsi family of Modena (who would move the operation to their home turf by 1939) and a fresh resolve to reenter Grand Prix competition.

Ernesto, who was the best designer among the brothers, created the 8CTF. The name stood for eight-cylinder competition testa fissa, or “fixed head,” meaning that the valve seats and combustion chambers were integral with the cylinder block. It was a DOHC straight eight with twin Roots superchargers that produced 350 (gross) horsepower at 6300 rpm from just 3.0 liters. The chassis featured an independent front suspension (with longitudinal torsion bars) and quarter-elliptic leaf springs at the back.

The first two cars, chassis 3030 and 3031, appeared for the Tripoli Grand Prix on the lightning-fast Mellaha circuit in May 1938. They immediately created a sensation in the hands of Count Felice Trossi and Achille Varzi. Masterpieces in cast and polished aluminum, the cars proved to be as quick as they were beautiful. Unfortunately, the minuscule size of the Maserati operation had forced economies in testing and development that were to haunt their entire campaign. Varzi broke his transmission on lap seven and Trossi retired with the same difficulties four laps later, after leading the Mercedes and Auto Unions and setting the fastest lap of the race. This was to establish a pattern for the cars—Trossi, on the pole at Livorno but didn’t finish; Pescara, the race lead and fastest lap before retiring.

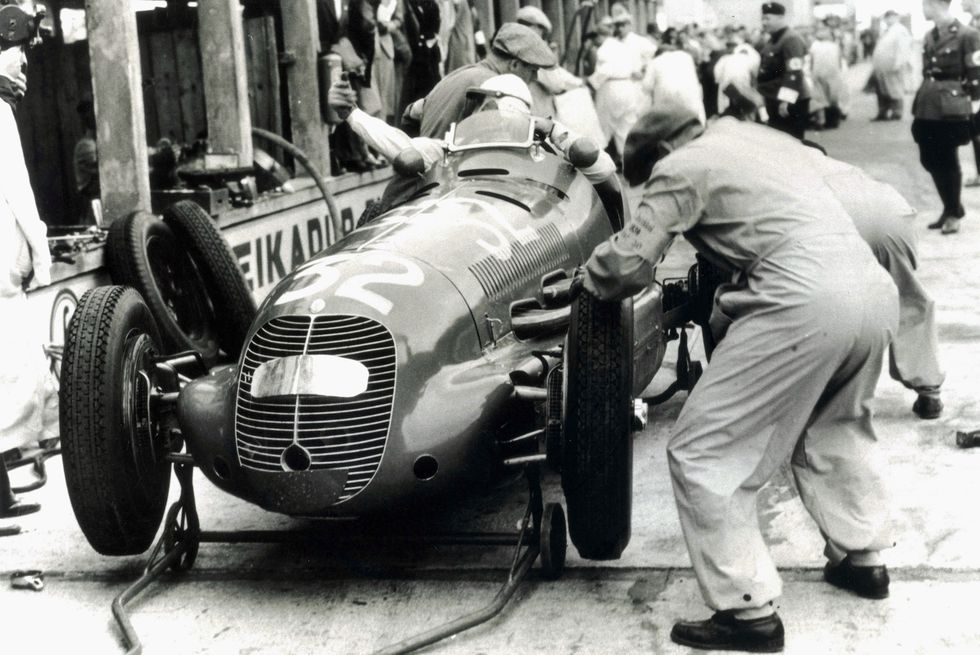

By September, a third chassis (3032) was completed for the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Goffredo “Freddie” Zehender crashed, bending the car slightly, while Trossi got as high as third before being disqualified.

Despite their erratic performance, the 8CTFs were attractive to many Americans, who had seen four of the older V8RI single-seaters perform well in 1936–37 and believed that a modern European GP car could win at Indy. During the early spring of 1939, Cotton Henning, the chief mechanic for Chicago union boss “Umbrella Mike” Boyle, purchased chassis 3032 and a spare engine. This machine, with some modifications for the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, was to carry the great Wilbur Shaw to two consecutive victories (1939 and ’40), with a third in 1941 prevented by a broken wire wheel.

German driver Paul Pietsch reached a high-water mark with 3031 in the 1939 German GP at the Nürburgring. He led the race against the full might of the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union teams, but finished third because of repeated failures of the Maserati-manufactured spark plugs.

By this point, Lucy Schell, who was now running Ecurie Bleue following a highway crash that badly injured her husband, had tired of Delahaye’s uncompetitive cars. She purchased the two remaining 8CTFs: chassis 3031 and 3030. Both were entered for the Swiss Grand Prix in August, where Dreyfus soldiered home eighth in 3030 (the other car did not start). Less than a month later, on September 1, 1939, Hitler invaded Poland.

France and Great Britain declared war on Germany two days later. Dreyfus, like thousands of his countrymen, enlisted and was slated for officers’ training. But once Poland fell, the German panzer advances ceased and Europe lapsed into a seven-month hiatus that is recalled as the “phony war.”

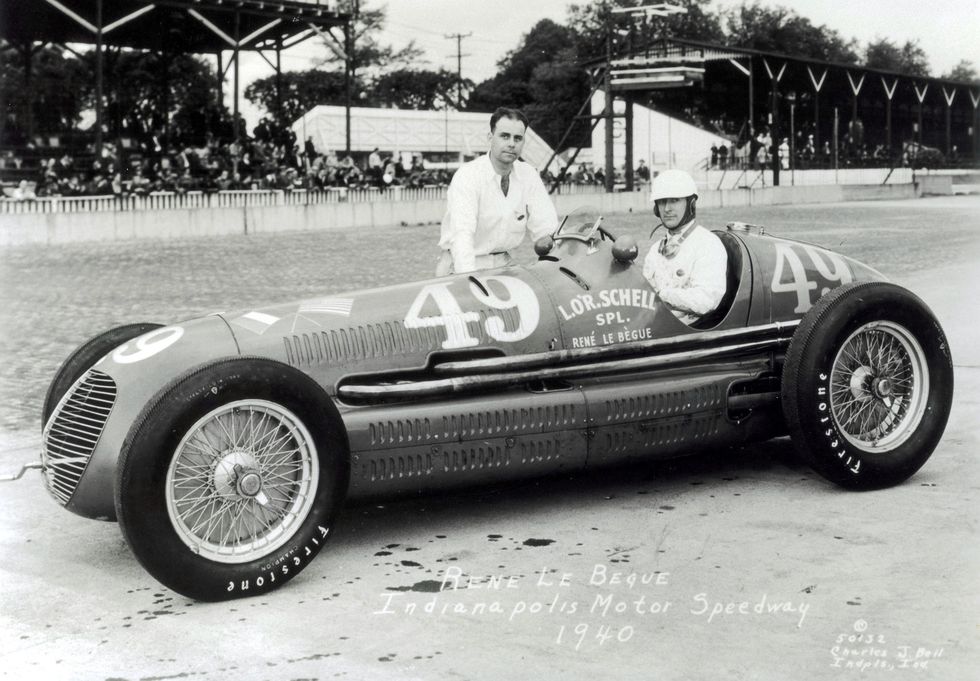

It was during this lull that Lucy Schell, widowed after her husband had been killed in a second road accident, decided to send her two Maseratis to the 1940 Indianapolis 500. Her intent was to perform well in the race and then to sell the cars, which already had a solid reputation based on Shaw’s victory the previous year. In early 1940, political strings were being pulled to give Dreyfus a 45-day furlough from his military duties. He would be joined by René LeBègue, a French sports-car and rally driver, who would serve as number two on the team.

The crew chief for the blue-painted Ecurie Bleue “Lucy O’Reilly Schell Specials” would be Luigi Chinetti, a transplanted Italian endurance-racing driver who had set up shop in Paris in the early 1930s. Chinetti, an ardent antifascist, had demurred in returning to Italy to join the Army, having served in the brutal Trentino campaign of World War I. He was more than happy to make what he considered a one-way trek to America.

Joining the little team on the sea voyage aboard the Italian liner Comte di Savoia was Lucy Schell’s 19-year-old son Harry, an American citizen who had been raised a Frenchman and spoke little English. In fact, none of the team was fluent and relied on Bernard Musnik, the New York-based correspondent for L’Auto, to act as interpreter. Lucy Schell, the instigator of the entire expedition, remained in France.

Dreyfus’s beloved France would never be the same, whether he returned or not. While they were at sea, Hitler’s hordes poured across the lowlands and drove the British Expeditionary Force back to the English Channel. The Ecurie Bleue contingent arrived in New York on May 23, and then flew to Indianapolis for practice and qualifying.

The brace of 8CTFs were completely unsorted regarding suspension setting and American fuel mixtures, and too-low gear ratios limited top speed. But the Frenchmen were greeted warmly by the Speedway establishment—especially by Shaw, who had his winning chassis 3032 perfectly tuned for the monster track.

In 1940, the fastest cars—including Shaw’s—were lapping at 127 mph. Both LeBègue and Dreyfus struggled to get past 118 mph with their hastily prepared cars. When qualifying ended, only LeBègue had squeezed into the field, in the 31st spot at 118.98 mph. Dreyfus, at 118.83 mph, was bumped by Billy Devore and Floyd Davis and relegated to second alternate starter.

How and why this happened remains something of a mystery. In his autobiography, Dreyfus claims he misunderstood the qualifying procedure. He thought, as in Europe, he had been guaranteed a starting position, and thus he did not exert full effort. This may be the case, although the notion that a driver as intelligent as Dreyfus would have remained that ignorant of the rules, regardless of the language barrier, appears doubtful. (Some believe he was disheartened by Shaw’s much faster lap times, as well as those of other American drivers he felt were inferior.)

No matter—Dreyfus redeemed himself in a roundabout manner. It was decided that he, as team leader, would share the driving with LeBègue, who would start the race and run the first 250 miles. Dreyfus would take over and presumably charge to a high finish. This appeared to be possible when he began to turn practice laps in LeBègue’s car at about 125 mph—perhaps overrevving the engine in the process. Then a connecting rod broke.

Dreyfus’s autobiography appears to conflict with the facts here. He states that he was driving his own car (3031), but Speedway records indicate it was LeBègue’s car (3030), and that in a desperate last-hour thrash Chinetti transferred Dreyfus’s good engine into LeBègue’s qualified machine.

They ran according to plan, with Dreyfus taking over while the car was in 10th place. His planned assault (which he believed might have carried him as high as fifth place) was halted when the final 50 laps were run under the yellow flag in a light drizzle. Wilbur Shaw won again in his Maserati, and the LeBègue-Dreyfus car motored home 10th.

While the Schell team was disappointed with their showing, the race results paled in comparison to the critical international situation. On June 17, the French sued for peace. It appeared that going home was impossible. Being unsympathetic to the French Vichy puppet government, Dreyfus ended up buying a restaurant in Closter, New Jersey, which he ran until December 7, 1941. The day after Pearl Harbor, he joined the United States Army and served with distinction in the European theater.

Following the war, he and his brother Maurice opened a restaurant called Le Gourmet in Manhattan. In late 1952, they started the famed Le Chanteclair on East 49th Street. Until the early 1980s, it was a watering spot for motorsport enthusiasts.

Chinetti spent the war in Manhattan as an imported-car mechanic and “enemy alien.” He ultimately became the U.S. importer for Ferrari. LeBègue did return to France and somehow managed to smuggle a Talbot GP back to the United States for the 1941 500. (It failed to qualify. He then went into the perfume business in New York.) Harry Schell entered prep school, then returned to Monaco to be with his mother. During the 1950s he became an accomplished, if second-level, Grand Prix driver before dying in a 1960 crash at Silverstone, England.

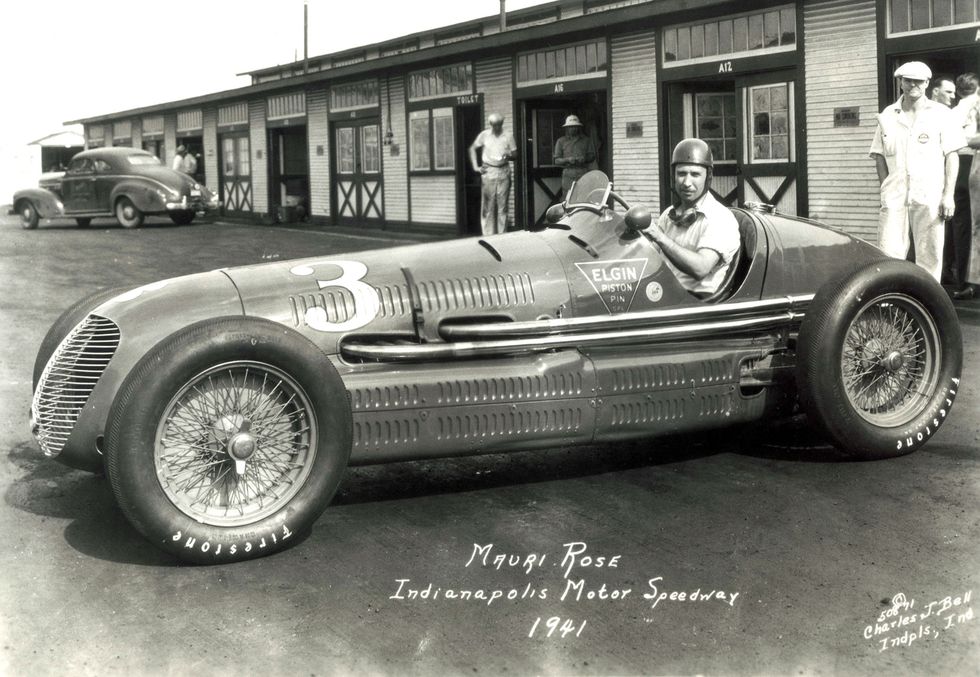

Following the 1940 race, Lucy Schell sold both Maseratis to former racing driver and car owner Lou Moore. With a year to tune them for oval-track racing, Moore was able to at least demonstrate the 8CTF’s potential. With Elgin Piston Pin sponsorship, the talented Mauri Rose behind the wheel, and a taller ring-and-pinion gear, chassis 3031 gained the pole position for the 1941 Indy 500 at 128.69 mph. After the car retired with ignition trouble at 60 laps, Rose took over for Floyd Davis, who was mired mid-pack in an Offenhauser-powered car also owned by Moore, and won the race. The second former Ecurie Bleue car, 3030, was driven by Duke Nalon, who started 30th and struggled to finish 15th.

When racing resumed in 1946, the Dreyfus car was sold to one R.A. Cott of the Federal Engineering Company in Detroit for driver Russ Snowberger, who started 10th at Indy and finished 12th. Louis Unser won the Pikes Peak hillclimb in the car in 1946 and 1947. By 1949, the Maserati eight-cylinder had been replaced by an Offenhauser four-cylinder which stayed in the car until 1951.

Its final outing at Indy came in 1953, with its original engine back in place. Now 15 years old, the veteran machine failed to qualify (as it had since 1950) and drifted into limbo.

The car’s recovery began when English Maserati enthusiast and collector Cameron Millar purchased 3031 and began its restoration and active vintage racing career in the 1970s.

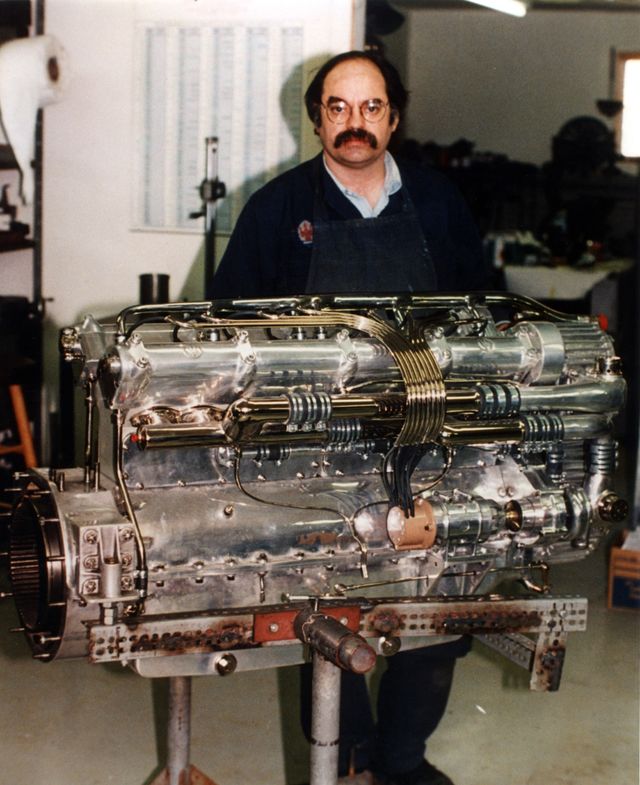

In 1982, Millar sold the Maserati to Joel Finn, who ranks among the world’s top vintage-car collectors, historians, and racers. He and his chief restorer, John Rogers, began a laborious 10-year project to bring the old car back to its former glory. It required all of Rogers’s prodigious talent as a machinist and fabricator. The engine was in particularly rough shape. The complex blower drive on the lower Roots supercharger was bent and seized. New valve guides had to be machined and set in the fixed head by employing a special jig and working with a mirror inserted through the exhaust ports. New bearings, rods, pistons, tappets, and valves had to be installed. Massive restoration of the body, which had been modified over the years, was required.

Rogers had just completed refurbishing Finn’s rare Mercedes-Benz 154/163 Grand Prix car when he set to work on the Maserati. He found amazing contrasts between the two contemporary machines. “The Mercedes was big, tough, almost crudely military,” he recalls. “But the Maserati was like a sculpture. The aluminum was cast as if it was going to a car show rather than a race. The fabrication, considering the time that it was built and the size of the Maserati operation, was beyond belief.”

While Finn and Rogers were toiling to restore chassis 3031, another top-rank collector, Bob Rubin, was completing the second Schell car, chassis 3030. The restoration was done by Chris Leydon of Lehaska, Pennsylvania. Each owner attempted to replicate the cars during different periods; Finn painted 3031 in the red livery of the Maserati brothers as the car last ran for the factory at the 1939 German Grand Prix. Rubin and Leydon dressed 3030 in the Ecurie Bleue colors, as it appeared at Indianapolis one year later.

The Shaw car (3032), is a centerpiece of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum’s collection.

The Finn and Rubin cars were brought to the Milwaukee Mile this past summer for a reunion of prewar Indianapolis cars. There they electrified the gathering with the unearthly screech of their supercharged straight eights. The memory of the great machines and their extraordinary journey to America has once again been revived.