Ask someone at random to name a hybrid car, and they’ll more likely than not say “Prius.” The Toyota Prius is by far the best-known hybrid-electric vehicle, and over two and a half decades, Toyota has sold roughly 6 million of them—and another 14 million (or so) hybrids of other models as well.

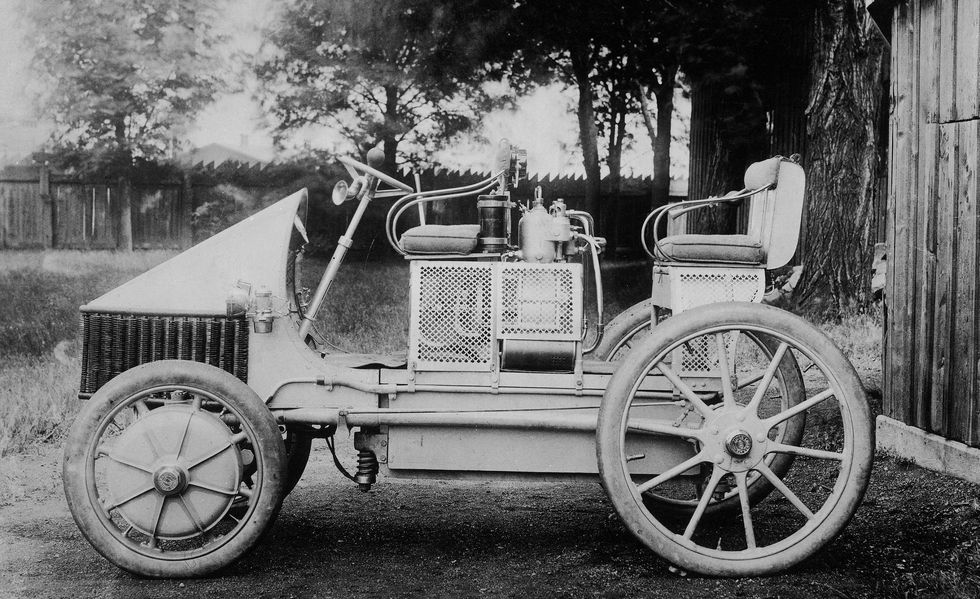

But the idea of a vehicle that blends a gasoline engine with electric drive didn’t originate with Toyota. In the first two decades of the 1900s, makers such as Owen Magnetic offered vehicles with both types of power. Equally significant, the very first vehicle to carry the Porsche name was a hybrid, the Loehner-Porsche “Mixte” of 1901—designed by a young Ferdinand Porsche. It remained obscure, the answer to an automotive trivia question, until Porsche started selling hybrids. At that point, its fame surged as Porsche marketing painted it as an antecedent of the 2010 Cayenne S Hybrid.

In most cases, these early models were series hybrids, meaning the engine acted solely as a generator to produce electricity that powered motors that turned the wheels. (This idea has lately been resurrected in the Ram 1500 Ramcharger, a battery-electric truck with more than 100 miles of battery range and a 3.6-liter V-6 “generator”—otherwise known as an engine—under the hood to power it for several hundred more miles.) But the added complications of electric motors, batteries, relay banks to control speed, and a host of other components meant early hybrids were both very heavy and very complicated. Gasoline alone won out.

Enter the Prius

Fast forward to the early 1990s, and a challenge set for Toyota engineers: engineer a practical four-seat car for everyday use that would consume only half the gasoline of comparable models in the lineup. It was a huge challenge for a company viewed as superb at production technology and quality, but hardly an innovator. And Toyota had its own moments of “production hell,” to use a phrase once promulgated by Tesla’s CEO.

The first production Prius in 1997 was sold only in Japan. It was a subcompact four-door sedan, but its fuel economy—especially in largely low-speed Japanese usage—was higher than anyone had seen. I’ve driven one of the Japanese originals; it was very slow, rather noisy, and the transitions among various modes of power weren’t always smooth. A revised version entered the North American market in 2000.

The Prius used what was known for a time as Hybrid Synergy Drive, with two electric motors and a planetary gearset that replaced the transmission. The engine and one or both motors delivered power under different circumstances and, crucially, one motor acted as a generator to recapture otherwise wasted braking energy when the car was slowing down. A nickel-metal-hydride battery pack with 1.3 kilowatt-hours capacity stored this recaptured energy, and at low speeds the Prius could operate as an EV for up to one mile, without the engine involved in any way.

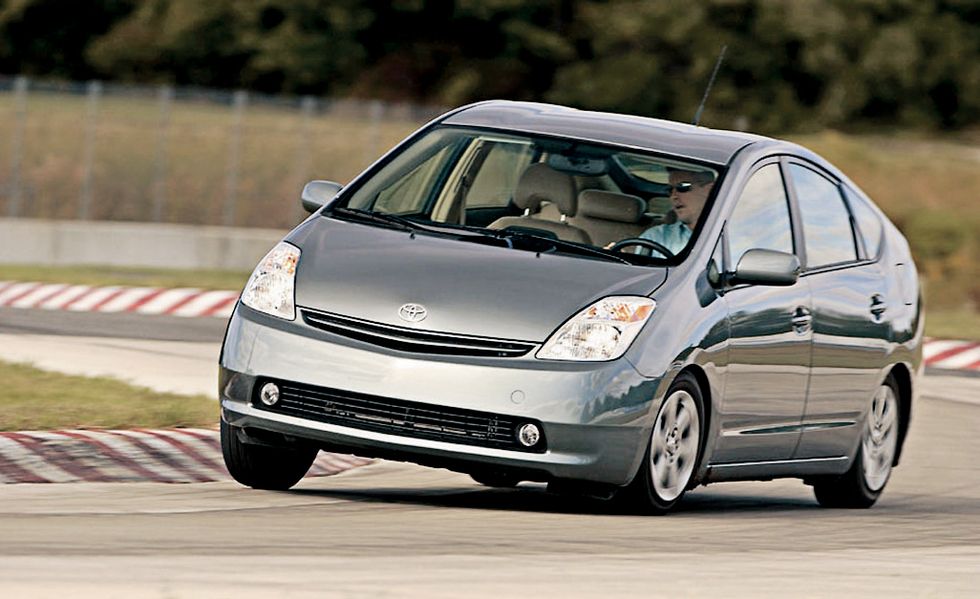

It was the second-generation Prius, introduced in 2004, that brought the model into the big time. Enlarged to compact size, the five-door hatchback was extremely aerodynamic for its time—and in the States, it launched into an era of sharply rising gasoline prices, making its EPA ratings of 40 mpg or more all the more striking. As a vehicle with the most technically sophisticated powertrain you could buy, it became a status symbol among tech-forward buyers and Silicon Valley moguls. It stayed there until the Tesla Model S displaced it starting in 2012.

A third generation of Prius in 2010 largely iterated on the second; the styling of the fourth generation in 2016 was widely acknowledged to be . . . well, let’s say polarizing. From one extreme to the other, the fifth generation for 2023 is much better looking and that still delivers the same fuel economy—and has a Prime plug-in-hybrid variant to boot with 39 to 44 miles of electric range.

Honda’s Minimalism, Ford’s Crossover

Another Japanese maker, Honda, beat Toyota to the hybrid punch by launching its Insight in the U.S. during 1999, a few months before the Prius. But the Insight was a tiny, two-seat, highly aerodynamic little hatchback, and its Integrated Motor Assist (IMA) system used a 13-hp electric motor between the transmission and a 1.0-liter three-cylinder engine. The motor added boost and captured energy from regenerative braking, but the IMA system couldn’t power the car on electricity alone.

Honda evolved this system throughout the 2000s, using it in the Civic Hybrid—which sold well—and then a second-generation, five-door hatchback Insight. That subcompact Insight hit the market the same year the third-generation Prius did, and the latter outsold it through the two cars’ run. Honda switched its hybrid efforts to a two-motor system that could provide electric-only propulsion like the Toyota system, though it’s a completely different arrangement.

Meanwhile, under then-CEO Bill Ford, the Ford Motor Company launched a hybrid version of its Escape compact crossover utility vehicle in 2005. Its system was similar to Toyota’s, though Ford swore it had been developed independently. (A patent dispute between the two was eventually resolved through the agreement that each company would license some technology to the other.)

The Ford Escape Hybrid gave the market what it increasingly wanted by 2005: an SUV with optional all-wheel drive. Throughout the Escape Hybrid’s eight-year run, half of production was sold with mechanical all-wheel drive, making it very popular in markets with winter weather. Ford beat Toyota by a year with an AWD hybrid; the Highlander Hybrid launched for 2006.

As for the other two Detroit makers, GM had experimented with hybrids in the late 1960s, but its XP-993 remained solely a concept and it focused development on its stillborn Wankel rotary engine. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that it developed a Two-Mode Hybrid system for its full-size pickup trucks and SUVs. With two electric motors, two or three planetary gearsets, multiple clutches, and a large 2.4-kWh nickel-metal-hydride battery pack, the system (downsized from one developed for transit buses) was both fiendishly complex and brutally expensive—an insider told me the cost to GM of its components was around $10,000. It delivered a major boost in fuel economy— from 14 to 20 mpg combined, which saved far more actual fuel than a Prius replacing a Corolla—but “20 mpg” didn’t sound impressive when a Prius delivered almost 2.5 times that number. Only 30,000 Two-Mode Hybrids were sold among five different models from Chevy, GMC, and Cadillac.

Chrysler too used a version of the system in its Dodge Durango and Chrysler Aspen Hybrids, of which only a few hundred were built before those two vehicles ended production as the company careened toward bankruptcy. BMW and Mercedes-Benz also developed their own versions of the Two-Mode Hybrid, used in versions of the BMW X6 and the Mercedes-Benz M-Class only for a couple of years before the entire cooperation was dissolved.

Adding a Plug

GM’s development work on the Two-Mode, however, contributed to the system used in the Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid that launched for 2011. Plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) remain misunderstood and hard to explain to average shoppers, but the compact five-door hatchback Volt was greatly beloved by its buyers over two generations through 2019. GM ended production of the Volt to prioritize the development of battery-electric vehicles, a bet that has yet to pay off.

Other plug-in hybrids are evolved from standard hybrid models, including three generations of PHEV Priuses and the RAV4 Prime. Chrysler (now Stellantis) has sold plug-in hybrids since 2016 (the Pacifica) and is rolling out 4xe PHEV versions of all its Jeep models, starting with the Wrangler three years ago.

Hyundai-Kia too has rolled out hybrids across many of its lines, but it uses a single e-motor between the engine and transmission—a much more powerful version of the same arrangment Honda used for its IMA a decade earlier. Its first Sonata Hybrid in 2013 was lumpy to drive, but the company has continuously refined its software and today they’re as good to drive as any single-motor hybrid system could be. It has adapted its system for plug-in-hybrid use as well.

These days, more and more hybrids are offered in a wider variety of vehicles. Toyota remains the leader and the highest-volume seller, but the technology has largely become a powertrain option rather than a type of vehicle. Most hybrids on sale today are identifiable only by their badges, and the days in which one was immediately obvious on the road—because hybrids were their own model lines—are all but gone. Only the Prius remains.

John Voelcker edited Green Car Reports for nine years, publishing more than 12,000 articles on hybrids, electric cars, and other low- and zero-emission vehicles and the energy ecosystem around them. He now covers advanced auto technologies and energy policy as a reporter and analyst. His work has appeared in print, online, and radio outlets that include Wired, Popular Science, Tech Review, IEEE Spectrum, and NPR’s “All Things Considered.” He splits his time between the Catskill Mountains and New York City and still has hopes of one day becoming an international man of mystery.