From the February 1997 issue of Car and Driver.

Chevrolet has presented new Corvettes that have stimulated our cranial synapses with exotic new technology, elevated our pulses with bump-and-grind styling, and sent our adrenal glands into overload with tire-scorching performance, but this new 1997 model is the first Corvette that presses all of our livable and useful buttons with its relentless attention to detail and meticulous engineering.

Dubbed the C5 because it is the fifth-generation Corvette, the new model uses a structure that is four times as stiff as the C4 chassis. Its natural frequency measures 23 hertz, close to the Mercedes E320‘s and the Oldsmobile Aurora’s, which are among the stiffest cars in the world. Furthermore, this stiffness only drops to 21 hertz when the roof panel is removed.

The stiffer structure does much to reduce the squeaks and rattles that have always plagued Corvettes, but chief engineer Dave Hill didn’t stop there. From day one, he assigned an engineer to do nothing but optimize the design and assembly of every part to eliminate unwanted noise. Among the items eliminated were 34 percent of the total number of parts in the C4. By using fewer, larger parts, the C5 is inherently more solid.

Despite the reduction in the number of parts, the C5 has grown: slightly on the outside, substantially inside. In addition to offering more room for large people, a lower sill and a taller roofline make it easier to enter and exit. The pop-out roof panel is now attached with three hand levers rather than four bolts and a ratchet wrench. Meanwhile, luggage space has doubled to 25 cubic feet, more than a Saab 900’s.

Completely new suspension geometry at both ends has greatly reduced the C4’s tendency to be pummeled by potholes, deflected by crowned roads, and upset by truck grooves on the road. The new model seems glued to the road, without transmitting all surface imperfections to its occupants.

As valuable as these improvements are, however, they would be worthless had they been achieved at the expense of performance. We’re happy to report that in the pursuit of their kinder and gentler priorities, Dave Hill and his team have not forgotten that speed is central to the Corvette experience.

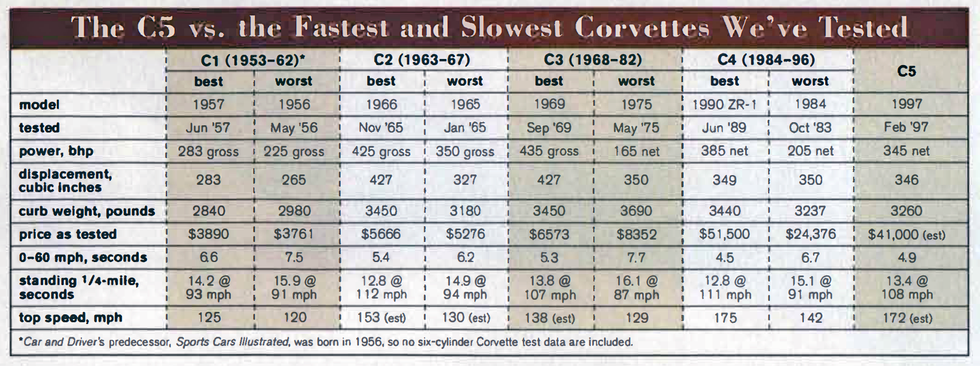

Despite a softer launch at Atlanta Dragway than we normally achieve at our sticky test track in Michigan, the preproduction 1997 Corvette hit 60 mph in 4.9 seconds and 100 mph in 11.4 seconds and swallowed up the quarter-mile in 13.4 seconds at 108 mph.

We were only able to reach 130 mph within the short confines of the drag strip, and that figure came up in 20.5 seconds, but Chevrolet claims a top speed of 172 mph. Jim Ingle, a Corvette development engineer and known straight shooter, assured us that he’s seen 175 mph at the 7.5-mile Transportation Research Center’s oval in Ohio.

The quickest LTl-engined C4 we’ve ever tested needed 13.6 seconds at 104 mph to cover the quarter. The fastest one topped out at 161 mph. Even the hotted-up LT4-engined car we tested last year could only run 13.7 at 104 and top out at 168. In fact, we’ve tested relatively slow ZR-ls that could barely keep up with the new CS. Despite its newfound comfort and practicality, the CS is, without question, one of the fastest Corvettes ever.

This combination of speed, utility, and solidity is clothed in completely new bodywork—still fiberglass, of course—that is both sleek and reminiscent of past Corvettes. To many eyes, however, there are a few styling genes from the Mazda RX-7 and Pontiac Firebird evident in its low, rounded, twin-nostriled front end.

In profile, the CS is low in front and a little heavy in the rump, as if it were mid-engined. Practically speaking, the low nose enhances forward visibility and the high tail reduces drag and increases luggage space, but the look takes a bit of getting used to.

At the rear, this bodywork terminates in a sharp crease that seems incongruous with the rounded contours elsewhere. The necessarily tall rear fascia is nicely broken up by four oval taillights near the top and an array of slots near the bottom. Unfortunately, the four flat-black exhaust tips virtually disappear when viewed from a distance. A few square inches of polished stainless steel would find a good home here.

Despite these nits, we don’t dislike the look of the CS. It just doesn’t knock our socks off. But pretty is as pretty does, and the new body boasts an excellent drag coefficient of 0.29—a useful improvement over the C4’s 0.34 figure.

Some of this benefit is offset by the greater frontal area, a result of the C5’s being 1.4 inches taller and 2.9 inches wider than the C4 (it’s almost as wide as the discontinued ZR-1). Allowing for this increase, the C5 still produces about 8.5 percent less aerodynamic drag than its predecessor. Lift—and the resulting high-speed instability that it can provoke—was never a problem with the C4, but insiders report that the C5 body is about 30 percent improved by that measure as well.

This coachwork covers a completely redesigned chassis that was conceived to finally give the Corvette the solid foundation it needed to shed its reputation for a jittery ride and low-quality assembly. Greater interior space, easier entry and exit, and a more solid mounting for the suspension pieces were also high on the new chassis agenda.

A folded-steel backbone—roughly 12 inches high, 9 inches wide, and 4 feet long—forms the heart of this frame. With a bottom plate attached by 36 bolts turning it into an enclosed tube, this structure provides immense torsional rigidity.

The sheetmetal flares out at each end to tie into the C5’s second major structural element: a pair of hydroformed rectangular-section steel rails that run the full length of the car, just inside the front and rear wheels and kicking out to form the door sills next to the passenger compartment.

These galvanized-steel elements begin as six-inch-diameter tubes. They are first roughly bent to shape and then inserted into a set of dies. The tubes are then filled with water at a pressure of 5000 psi, which forces them into their four-by-six-inch rectangular configuration. They provide much of the C5’s bending stiffness.

A steel roll-bar structure is welded to the rear intersection of these frame rails and the backbone frame. At the front intersection, two rectangular steel tubes jut upward to provide mounting points for the aluminum windshield structure.

Featherweight pieces are everywhere on the frame. The steering column is supported by a magnesium casting. The removable roof panel also uses magnesium for its frame. The floor boards are a composite of fiberglass and balsa wood. No one can accuse Hill and his team of taking shortcuts in the design of this chassis.

One might, however, come to a different conclusion after a first glance at the new LS1 engine, which superficially appears to be another rehash of the 31- year-old small-block V-8. But the LS1, which we thoroughly discussed in Technical Highlights last October, shares nothing but its 4.4-inch bore spacing with its forebears.

The light-but-strong philosophy that pervades the CS is evident in the LS1 engine as well. Its new aluminum block extends well below the crankshaft centerline and uses six bolts (four from the bottom and one from each side) to retain each main-bearing cap. Each aluminum head attaches to this block with 10 bolts in a symmetrical four-bolt pattern around each bore, rather than the traditional five-bolt array. These bolts thread into the block down near the main-bearing web to minimize distortion of the cylinders bores when they are tightened.

These new heads employ equally spaced intake and exhaust ports rather than the traditional siamesed pattern. The lightweight plastic intake manifold takes advantage of this change with tuned intake runners and smooth interior surfaces.

The LS1 engine marks the debut of the Corvette’s first drive-by-wire throttle. Instead of a mechanical linkage from the accelerator to open and close the throttle, the LS1 uses an electric motor. This motor is controlled by a computer that reads the position of a sensor at the accelerator pedal. It also incorporates the cruise-control system and communicates with the engine-management computer and the traction-control system to restrict engine output when needed. By combining all these functions, it is actually simpler and lighter than the conventional setup.

In contrast to this innovation, you might be surprised to see that the LS1 engine retains the traditional pushrod, two-valve design. But lightweight valves, extensive use of roller bearings, and optimized valvetrain geometry have reduced friction while maintaining a lofty redline of 6000 rpm.

Moreover, the LSI is distantly related to an upcoming new truck V-8, which will be built in huge volumes. That genealogy may well have dictated the pushrod setup as well as the tight bore spacing that forces the LS1 engine to have a smaller bore and longer stroke than the old V-8.

But with 345 horsepower and 350 pound-feet of torque, a light 532-pound weight, compact dimensions, and projected EPA fuel-economy figures of 18 mpg city and 28 mpg highway with a manual transmission, it’s hard to fault Chevy’s design decisions.

This engine feeds its output to the rear wheels via an all-new driveline that positions the transmission in the tail. A torque tube that is five inches in diameter and four feet long connects the engine rigidly to the new rear-mounted transaxle. The entire assembly attaches to the chassis via a hydraulic mount underneath the transaxle and a motor mount on either side of the engine block.

With a manual transmission, the hydraulically operated clutch is bolted to the engine’s flywheel. The clutch in turn twists an aluminum-and-ceramic-matrix driveshaft. The gearbox is a variation of the Borg-Warner T56 used in the Chevrolet Camaro and Dodge Viper. For use in the CS, its guts are reinforced with triple cone synchronizers in the lower gears and stuffed into a new case that bolts to a Getrag limited-slip differential.

If you’re being picky, this isn’t really a transaxle, since the transmission and the differential each have their own discrete cases and do not share lubricants, but other than costing a few pounds and maybe an inch in length, that’s not a disadvantage.

If you specify an automatic, the arrangement is much the same except that the torque converter is mounted in the rear with the transmission, a Hydra-Matic 4L60-E, which is a repackaged version of the C4’s four-speed automatic.

By moving the transmission from the front to the rear, Hill and his engineers created more space for wider footwells—six inches wider on the passenger side. Moving the transmission aft also helped restore the weight distribution to nearly even—it was 51.4/48.6 on our test sample—after such measures as pulling the rear wheels back, moving the gas tank forward, and eliminating the spare tire had increased the front weight bias.

The keen reader will have noticed the implications of the hydraulic mounting of this differential. Since 1963, when Corvettes first received independent rear suspensions, their differentials were always solidly mounted because the half-shafts formed the upper suspension links. On the CS, this is no longer so.

Instead, the rear suspension consists of unequal-length aluminum upper and lower control arms with a rear-mounted toe-control link. The lower control arms mount to a cast-aluminum subframe that is bolted solidly to the chassis. The upper control arms attach to the hydroformed side rails. The half-shafts are now a splined design to accommodate the length variations imposed by suspension movement. A transverse plastic leaf spring is the only element even vaguely recognizable from the C4.

The suspension geometry was conceived to provide minimal track and toe changes as the wheels move up and down. The toe-control link is critical to achieving this, especially since the bushings allow the wheels to move rearward slightly to help absorb small, sharp bumps.

In front, the design philosophy is similar, with unequal-length control arms and a transverse plastic leaf spring mounted to another large cast-aluminum subframe. In place of the toe-control link, you’ll find GM’s Magnasteer II setup.

Magnasteer II is a refinement of the rotary electromagnetic variable-assist power-steering system that made its debut on the Aurora. The computer that controls this electromagnet now looks at speed and lateral acceleration to provide a more stable, progressive feel at the steering-wheel rim.

The base suspension has gas-charged, single-tube shock absorbers all around. Optional is the F45 variable-damping system that provides three cockpit settings. Each setting corresponds to a different program that selects from an infinite variety of damping curves based on wheel travel, steering-wheel angle, and calculated lateral acceleration. Called Selective Real Time Damping, the system can change the shock settings as often as 100 times per second.

Finally, for committed performance enthusiasts, there’s the Z51 option that comes with larger (1.8- versus 1.4-inch diameter) gas-charged shocks with a single setting (stiffer than any of the F45 offerings), along with stiffer springs and larger anti-roll bars.

As on the C4, there are vented disc brakes and aluminum calipers at each corner. Although the front rotors are slightly smaller in diameter than previously, they are substantially thicker, as are the rears. Furthermore, the two openings in the C5’s front fascia feed cooling air via four-inch ducts to the front brakes. Anti-lock control is provided by a Bosch ABS V system that is integrated with the standard traction-control system.

All this chassis hardware communicates with the pavement via Goodyear Eagle F1 GS EMT tires—P245/45ZR-17 in front and P275/40ZR-18 in the rear. You will notice that for the first time in Corvette history, the rear tire is larger in diameter than the front, for appearance and because the resulting longer contact patch provides some stability benefits.

You might also notice that both tires are one size narrower than the C4’s, although we were told that the new car achieves 0.92 g on the skidpad compared with 0.89 for the old one. With sufficient grip, the narrower tires provide better steering feel and greater tolerance of imperfect pavement.

Sliding behind the wheel of the C5 certainly demands less human origami than before, and the greater view out from the cockpit makes the C5 feel more like an Acura NSX than the C4 with its somewhat buried perspective.

Ergonomically, the C5 is hard to fault. The wider footwells provide room for a perfectly positioned dead pedal. The wipers are controlled by a stalk sprouting from the right of the steering column. The steering column itself is adjustable for angle, although not reach, and comes with a fat, grippy rim and spokes well positioned for hands at the three- and nine-o’ clock positions. The shift knob is no more than a hand’s breadth away from the rim. The ignition switch is on the dash rather than the steering column.

And to our immense relief, the C5 has a full set of proper, round, white-on-black instruments that are neither a weak imitation of an arcade game nor afflicted with any needles that fall as the temperature rises.

Not that there’s a total absence of razzle-dazzle. When you fire up the C5, the needles on all the instruments flick full scale and back, and a driver-information center uses an alphanumeric display to communicate a wide variety of information, including the individual pressure in each of the C5’s four tires (good to know because an inattentive driver might not realize when the run-flat tires are underinflated).

As you accumulate miles in the C5, the claims about the improved rigidity become fully credible. Bumps produce single, muted thumps with no quivers, no rattles, and no aftershocks. There’s also no sign of the C4’s fondness for continuous tiny vertical shakes that made us feel as if we were sitting on the end of a springy diving board. Finally, the C4 suspension’s tendency to turn vertical bumps into small, lateral vibrations—occasionally even on a straight road—is completely absent.

The preproduction examples we drove did, however, exhibit more driveline noise than we expected. In one, the engine buzzed lightly between 3000 and 5000 rpm. In another, there was some rattling in first gear. With the C5’s sophisticated driveline isolation, we hope these vibrations will be exorcised before cars arrive at dealerships.

When you start pushing the C5 hard on a winding road, the body moves up and down as needed to absorb the bumps and grinds of the pavement, but the four tires feel as if they’re magnetically attached to the pavement.

In cars equipped with the adjustable F45 suspension, this supple character prevails in all three settings, although the level of ride control increases progressively as you dial the switch from “tour” to “sport” to “performance.” But even the tautest setting is far less harsh than it was on, say, the 1995 FX3-equipped models.

Such a stable platform encourages hard charging. The precise and progressive control responses will help all C5 drivers imitate Alain Prost. The lengthy shift linkage communing with the rear-mounted transaxle feels precise and accurate. The stopping power of the strong brakes varies linearly with the pressure of your foot on the cast-aluminum brake pedal. Furthermore, there’s a nice gradual onset of braking when your foot first starts pressing the pedal, making you look smooth even when you stab the brakes to cope with an over-the-rise surprise.

The steering proves equally friendly, although at first we felt that the effort was a little too heavy. But as we proceeded to attack the winding and hilly back roads of Kentucky, the steering became completely transparent. There seemed to be a seamless connection between the driver’s brain and the C5’s front tires without the need for any conscious thought. You can eat up pavement very quickly and easily in this car without ever breaking a sweat or sliding a tire. However, we were given the opportunity to do both at Road Atlanta racetrack. We were critically interested in the C5’s behavior at the limit, because the C4 was particularly forgiving when driven flat out. Despite its high limits, you could lean hard on it, safe in the belief that it would break away gradually and keep its tail in line.

We soon developed the same confidence in the C5, although with the new car’s higher grip, it definitely takes more speed before it slides. Through the 70-to-90-mph esses at Road Atlanta, the CS only gradually relinquishes its grip on the asphalt. Unlike the C4, the new model does slide first at the tail, but after oozing out only a few degrees, it stabilizes in a slight drift. Easing off the throttle a tiny amount brings the car right back into line.

In slower turns, such as the right-angle, second-gear corner leading onto the back straight, you can get the tail out big time if you are even slightly overaggressive with the throttle—with the traction control turned off, of course. Not even the Dodge Viper GTS demands as much respect in similar turns.

As it turns out, Corvette engineers plan a few changes prior to production to minimize this behavior. A five-percent-stiffer front spring will increase understeer slightly, and a change in the rear-tire compound is expected to increase cornering grip when the power is hard on.

Those who perennially hope for a smaller Corvette will be disappointed, but there’s no question that the CS uses its bulk well. Moreover, it is not overweight for its size or performance. The now-defunct Nissan 300ZX Turbo weighed 300 pounds more than this new CS, and the Toyota Supra Turbo and the Mitsubishi 3000GT VR4 are heavier than it as well. Only the far smaller Porsche 911 undercuts the CS’s weight—and then by less than 200 pounds.

Which brings us to another Corvette tradition that the CS upholds: exotic-car performance at a moderate price. The least expensive production car we’ve tested that can outperform the CS in the quarter-mile is the Dodge Viper RT/10, which costs $6S,260. Although final CS pricing has not yet been announced, Chevrolet plans to price it not much higher than the C4’s $38,000 base price.

Corvettes, of course, have always delivered tremendous performance for the buck. But purists have tended to dismiss this value by reciting the litany of quality and refinement shortcomings that accompanied it. With the CS, that list is suddenly very short indeed.

Specifications

Specifications

1997 Chevrolet Corvette

Vehicle Type: front-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2-passenger, 2-door targa

PRICE (ESTIMATED)

Base/As Tested: $39,000/$41,000

ENGINE

pushrod V-8, aluminum block and heads, port fuel injection

Displacement: 346 in3, 5665 cm3

Power: 345 hp @ 5600 rpm

Torque: 350 lb-ft @ 4400 rpm

TRANSMISSION

6-speed manual

CHASSIS

Suspension, F/R: control arms/control arms

Brakes, F/R: 12.8-in vented disc/12.0-in vented disc

Tires: Goodyear Eagle F1 GS EMT

F: 245/45ZR-17

R: 275/40ZR-18

DIMENSIONS

Wheelbase: 104.5 in

Length: 179.7 in

Width: 73.6 in

Height: 47.7 in

Passenger Volume: 52 ft3

Trunk Volume: 25 ft3

Curb Weight: 3260 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph: 4.9 sec

100 mph: 11.4 sec

1/4-Mile: 13.4 sec @ 108 mph

130 mph: 20.5 sec

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph: 5.5 sec

Top Gear, 30–50 mph: 11.6 sec

Top Gear, 50–70 mph: 11.7 sec

Top Speed (C/D est): 172 mph

Braking, 70–0 mph: 163 ft

C/D FUEL ECONOMY

Observed: 18 mpg

EPA FUEL ECONOMY

City/Highway: 18/28 mpg

Contributing Editor

Csaba Csere joined Car and Driver in 1980 and never really left. After serving as Technical Editor and Director, he was Editor-in-Chief from 1993 until his retirement from active duty in 2008. He continues to dabble in automotive journalism and LeMons racing, as well as ministering to his 1965 Jaguar E-type, 2017 Porsche 911, and trio of motorcycles—when not skiing or hiking near his home in Colorado.