Kevin Wilson first became interested in electric vehicles when he was a kid in 1960s Detroit. “We had a lot of family who were doing deliveries,” Wilson told C/D. “My dad drove a bakery delivery truck, and I had uncles who did mop and rug deliveries. And my grandfather would talk about driving an electric milk float [delivery truck] in Glasgow, Scotland, and shake his head about why they didn’t still exist anymore. He would say, ‘If you’re just going to go to do a 50-mile route and then park the car overnight, why the hell is it not electric?”

During his 35-plus-year career as an automotive journalist (including a three-year stint at C/D) Wilson covered nearly the entire timeline of our contemporary re-engagement with battery-powered cars, including the founding and rise of Tesla. Now that he has retired, he put his experience to good use, writing a new book “The Electric Vehicle Revolution: The Past, Present, and Future of EVs” (Motorbooks).

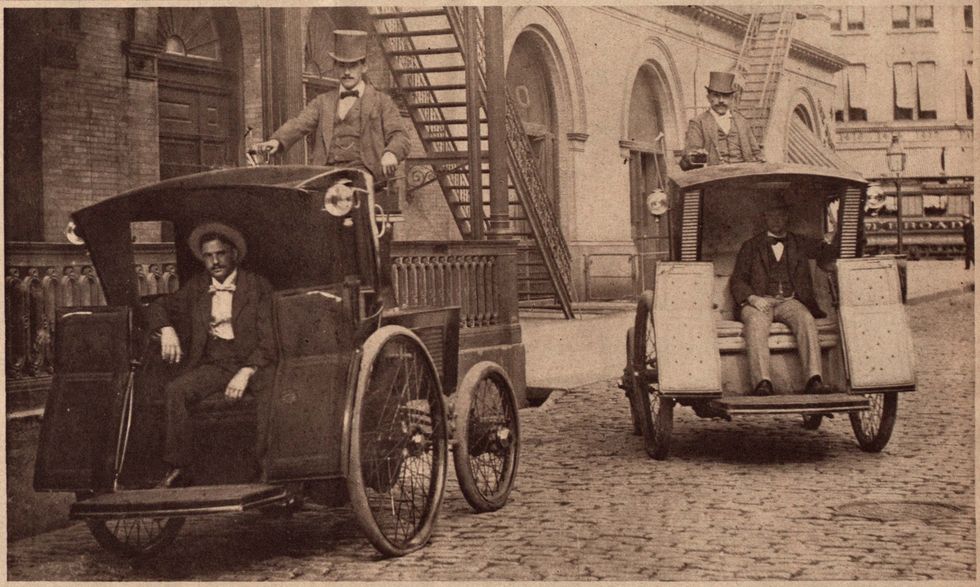

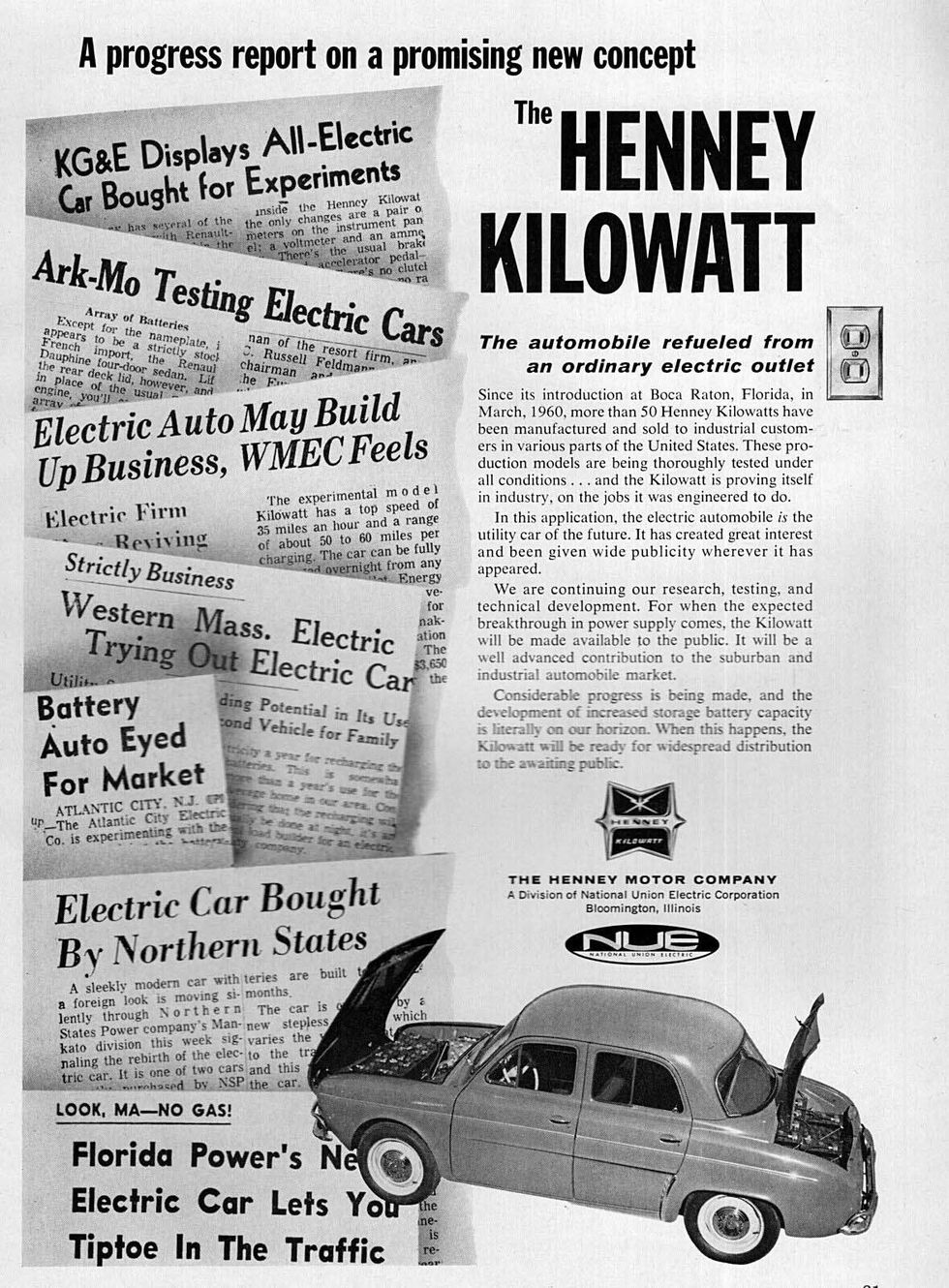

The book is a comprehensive survey of EVs, from the earliest examples back in the mid-19th century up to the present, broadly illustrated with archival photos and period advertisements, and full of stories and evidence of obscure marques—from Detroit Electric and Baker to Tropicana and Enfield—whose bizarre histories will delight you.

Particularly interesting are the sections on the very earliest electric vehicles, which pre-dated automotive applications of the internal combustion engine by decades, and those on early 20th-century EVs, which were marketed to racers, to urban fleets, and particularly to wealthy women, for whom the rough mechanical hand-cranking of early gas-powered cars was seen as unseemly or impractical.

“It worked best for taxis and short-term delivery,” Wilson says of early 20th-century fleets. “The New York taxi fleet was charged in a converted ice arena. They actually had equipment to swap out batteries.” And like today EVs, those of the early decade of the last century accelerated well and hit high speeds early. “The first car to reach over 100 kilometers-per-hour, and 100 mph, were electrics,” Wilson says.

Most interesting here was how close Henry Ford and Thomas Edison came to bringing an electric car program to market. “The New York Times archives had an interview with Henry talking in public about it being a year away,” Wilson says. “I had been vaguely aware of this collaboration, but was surprised by how close it came. Imagine that electrics, instead of being hand-built carriages for rich ladies, had been developed with Ford’s mass production/mass marketing mentality.”

We were also compelled by the sections on the mid-20th-century revival of interest in EVs, during our experimentation with other alternative propulsion sources such as nuclear or turbine, our deep-pocketed efforts to win the space race, and our search for fuel efficiency during the energy crises of the 1970s. “That mid-century period is a big one for EVs. People kept trying to make it work,” Wilson says. Hence, we saw electrified—and even production—versions of the Renault Dauphine, Chevrolet Corvair, Chevrolet Chevette, Fiat Ritmo/Strada, Renault LeCar, and Bradley GT, as well as low-run or experimental dedicated EVs like the Sebring-Vanguard CitiCar, the GE/Chrysler ETV-1, and GE 100.

Wilson was able to source a good deal of the book’s imagery from General Motors, Chrysler, and the National Archives. But he had to dig deeper for some of the more obscure examples. “The Automotive Hall of Fame Museum in Dearborn, Michigan—which is right next door to but unaffiliated with the Henry Ford—had some useful archival stuff,” Wilson says. “There’s a couple of interesting electric vehicle groups on Facebook that had some things. And Bill McGuire’s Mac’s Motor City Garage and the website OldMotors was also great.”

Wilson’s study of the past has provided him with an interesting perspective on the future of EVs. He’s bullish on plug-in hybrids: “If plug-in hybrids were used the way they’re meant to be used—like, actually plugged in—I think they’d be the best solution,” he says.

He sees a terminal point in our current battery chemistry. “Lithium-ion batteries are not a perfect solution. And since there’s so many alternatives on the horizon, I don’t think it’s going to be all that long before we start looking at lithium as a useful interval, but sort of a dead end, like the way people now look at nickel-metal hydride.”

And he doesn’t see full electrification as immediately imminent. “Many modern car people will say things like, EVs were a bad idea back then, and they’re a bad idea now,” Wilson says. “I guess the book does reflect my own goals and approach. Where many people seem to address it as an either/or question—either we’re going to have electric cars or have gas cars—I’m like, well, we can actually have both. And, the realistic view is that the switch to EVs takes a very long time.”

Contributing Editor

Brett Berk (he/him) is a former preschool teacher and early childhood center director who spent a decade as a youth and family researcher and now covers the topics of kids and the auto industry for publications including CNN, the New York Times, Popular Mechanics and more. He has published a parenting book, The Gay Uncle’s Guide to Parenting, and since 2008 has driven and reviewed thousands of cars for Car and Driver and Road & Track, where he is contributing editor. He has also written for Architectural Digest, Billboard, ELLE Decor, Esquire, GQ, Travel + Leisure and Vanity Fair.