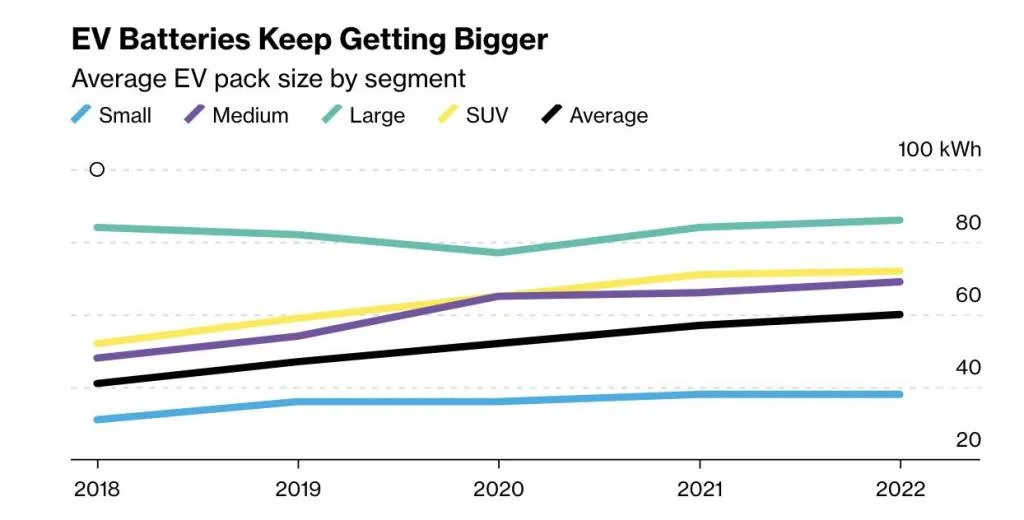

Electric vehicle battery costs soared in 2022. But that doesn’t seem to have slowed the pace of automakers planning to adopt ever larger battery packs to satisfy ever-higher EV driving range claims.

As Bloomberg recently calculated, using EV models from the U.S., Europe, and China, the average pack size is now around 80 kwh, from in the vicinity of 40 kwh in 2018, and the growth trend is expected to continue for some years.

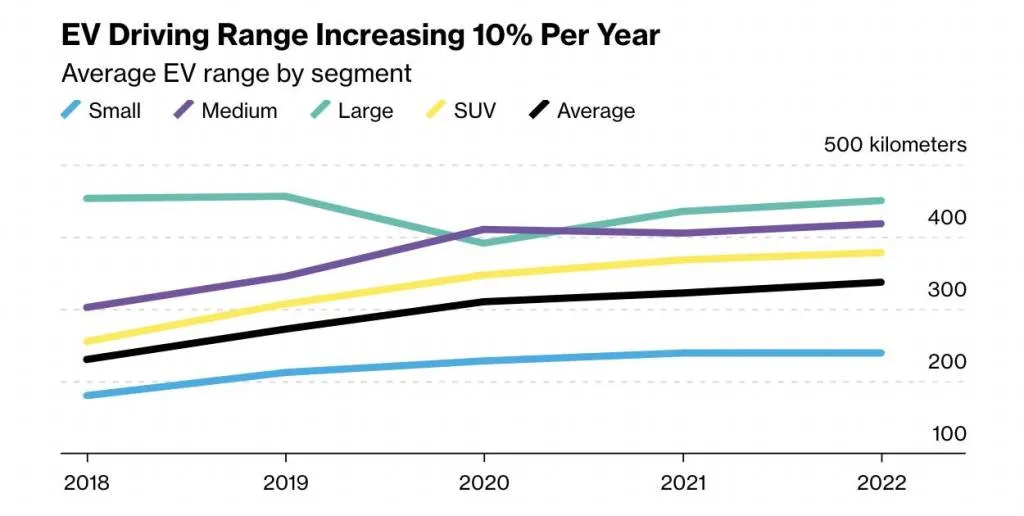

Meanwhile, average global EV range is now at 210 miles—up dramatically versus the average range of 143 miles in 2018.

That also means average EVs are less efficient, the byproduct of a shift to larger EVs.

EV driving range has been increasing at a rate of about 10% each year. Bloomberg sees the market finally reaching a ceiling in its demand for more range at 250-310 miles depending on the size of the EV, with the smallest city cars well below that range.

The largest EVs as a group are the one exception to the upward trend. They ended up at about the same driving range they offered five years ago—the result of Tesla boosting its larger models’ range while other larger EVs with lower range joined the market.

EV batteries over time – Bloomberg

EV range over time – Bloomberg

Bigger batteries, more range. Not a sustainable trend.

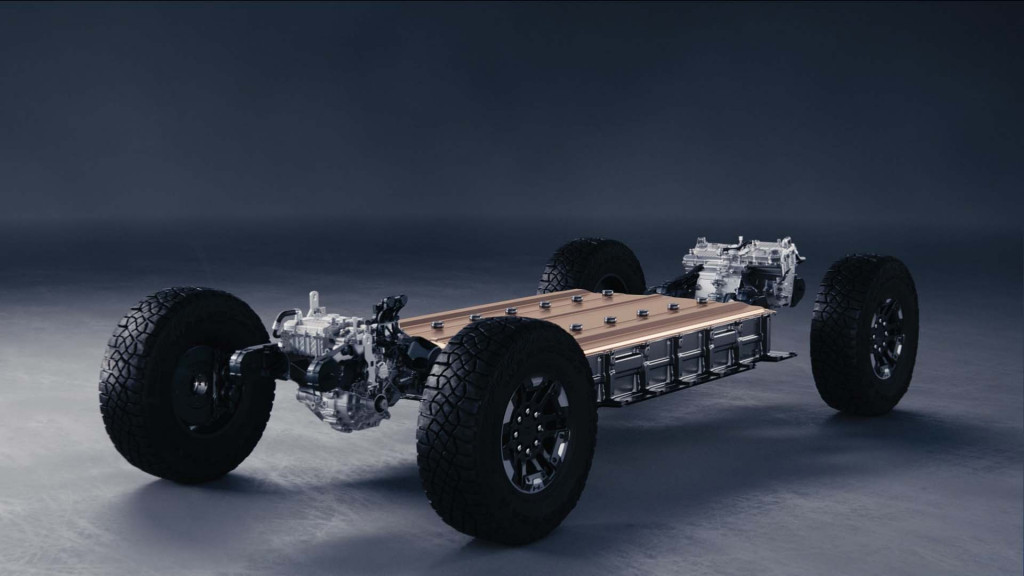

The sticker shock, it seems, is being built into big electric trucks such as the upcoming Chevrolet Silverado EV. In top-spec form, its most expensive building block, the battery pack, costs more to GM as a single part than the sticker price on several of Chevy’s entire vehicles.

According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, the Silverado EV’s pack, topping 200 kwh, represents $25,000 to $27,000 of direct cost to GM. That happens to be as much as a well-equipped 2024 Chevrolet Trax crossover, or a base 2024 Chevrolet Trailblazer SUV.

2024 Chevrolet Silverado EV with GM Ultium Home energy system

The Chevy Silverado EV won’t even have the biggest battery among full-size electric trucks. Ram plans a gigantic 229-kwh pack for its upcoming Ram 1500 REV.

The Silverado EV’s battery pack has more than twice the capacity versus that of the top Lucid Air that can go more than 500 miles on a charge. It’s also enough to power an average American house for almost three weeks, based on the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s 2021 household daily average of 10.632 kwh.

Ford isn’t going to go to 600 miles of range and thinks the sweet spot is around 350 miles. Mazda has said that long-range EVs aren’t the future.

2022 GMC Hummer EV

Battery bloat could push the market to burst

Bloomberg says that while this makes sense for automakers interested in selling more EVs now, “if left unchecked, this relentless rise in range and accompanying battery-pack sizes will eventually make it very difficult for the battery supply chain to keep pace.”

Considering the expected growth in battery size per EV, along with the expected growth of the EV market, Bloomberg suggests that battery demand in 2030 will be 50-70% higher, and that will put a direct strain on lithium supplies, although a shift to LFP cells will help soften the effect on cobalt. Without proper planning, the supply pinch could play out like the price spike that happened in 2021 into 2022, interrupting what had otherwise been a longtime drop in battery prices and thus a boost in EV affordability.

Besides, the gigantic battery packs add thousands of pounds of weight to vehicles, potentially becoming a safety liability to other road users and lowering efficiency and range per kwh.

2019 Tesla Model 3

Incentivizing smaller, higher-efficiency EVs

The push toward larger and larger battery packs isn’t limited to the biggest trucks. Automakers have been building bigger batteries into EVs of all sizes, as Bloomberg underscores. And even later this decade, developments like improved energy density or breakthroughs like solid-state cell tech are unlikely to provide a meaningful about-face on their own.

One simpler way to cut the dependence on super-size battery packs is by incentivizing vehicles that do more with less.

Right now, that’s not what U.S. rules and incentives do—especially not the EV tax credit.

2023 Mercedes-Benz EQE 350+

An aerodynamically efficient sedan costing $55,001 doesn’t qualify for the EV tax credit, even if it checks all the boxes for American assembly and the domestic supply chain. Meanwhile, a far less efficient SUV, likely with a much larger battery, costing $80,000 might qualify for the $7,500 EV tax credit. Furthermore, many luxury vehicles with even larger battery packs and lower efficiency—foreign-built or not—will qualify for a Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit that applies $7,500 of federal money to subsidize a lease.

Bloomberg also recommends deeper support from governments toward charging infrastructure. In the U.S., the $7.5 billion national EV charging network is part of that.

The federal government’s recent move to step in and tackle EV charger reliability might also help ease confidence in EVs with less built-in range. Also factor in that automakers, with the promise of being part of the buildout, are starting to participate more aggressively—with the seven-automaker joint-venture network announced in July perhaps due to be the first true rival to the Tesla Supercharger network.

Only time will tell if that will be enough to reverse the trend.